Inclusive Leadership

Considerations when hiring a chief diversity officer

More and more companies have been elevating diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) topics and the team associated with making DE&I a strategic priority in the wake of the #MeToo movement, calls for racial equity following George Floyd’s death in the United States, and efforts to make progress on gender equity in countries including France and Japan (to name just two). In just the past two years, for example, the share of diversity executives reporting directly to the CEO at Fortune 100 companies leapt from 2% to 14%. But simply hiring a chief diversity officer (CDO), even if they report to the CEO, doesn’t ensure sustainable success with DE&I—any more than hiring other leaders might ensure sustained success in changing behavior at scale in their areas of expertise. Indeed, a recent survey conducted by Heidrick & Struggles of executives from eight countries around the world found that only 58% say their companies are inclusive to a large extent.1 Some organizations have leveled out in terms of their progress on meeting specific DE&I goals, and others have even started to regress a bit despite genuine efforts. One common question is whether companies put too much focus on compliance as DE&I became more of a priority, rather than acting out of true belief that it was the right thing to do. This is a topic of ongoing debate that we will not try to address here.

Whatever the reasons, for DE&I leaders themselves, it’s a high turnover role.2 These leaders typically have little budgetary or governance control, which makes it hard to get things done; any issue that might create conflict at work (and these are multiplying rapidly) is now considered part of “inclusion”; and these leaders carry the expectations of large numbers of employees and face tough conversations every day. When these leaders exit their roles after a short tenure, it increases pressure on companies to figure out how to structure the role at the right level and support an effective person in it.

Overall, we believe that a change in the way CEOs and CHROs are defining both the CDO role and the capabilities they seek in a CDO is one step toward sustainable progress on DE&I. Companies should not establish a function without having thought through their level of ambition for their DE&I efforts, structuring the role so it will have the resources to meet the organization-wide goals for change that leaders and employees will be asking the CDO to meet, and ensuring the plan to onboard a new CDO will give them the best chance to succeed. However, success will also require the executive team to view the DE&I role as one among an entire leadership team responsible for progress. A CFO, COO, or chief legal officer cannot drive and ensure behavior change across a company on their own. A CDO is no different. And their task is further complicated because people often process issues related to DE&I through a personal filter before a business or work filter. Yet few people, even those on a single leadership team, know what other leaders really think or have taken the time to build the types of professional relationships with each other that enable them to work through issues where they might not agree but they need to make a decision. Leaders should also know that, even when all these conditions exist, it may be hard to convince employees, clients, or partners that a company is committed enough to DE&I until such time as it has material progress to report regularly.

Diversity leaders for today’s world

Succeeding with DE&I used to mean focusing on diverse hiring and, perhaps, seeking to remove bias from performance reviews. Diversity expertise was part of the talent management function and not much more important than any other subspecialty. Throughout the past decade, however, it’s gotten more complicated as evidence of how diversity supports business success and core beliefs about that has become more common in younger generations and as the number of characteristics of employees that many companies include in expanded efforts around D (constructing great teams) and E&I (cultures that reward being fair, inclusive, and welcoming of people, especially people different from you) has grown. Leaders, at the same time, have discovered that numbers and representation alone do not drive sustainable progress. In fact, many learn the opposite, which is costly: they learn that they can hire more diverse employees (of all kinds) and yet not retain them.

This retention problem has prompted companies to put more focus on inclusion as a dependent variable for succeeding with DE&I efforts, which requires succeeding with the much harder task of changing people’s behavior at scale. DE&I broadly is now at a turning point, similar to the shift that occurred toward gender-specific inclusion about 15 years ago: from trying to change women so they would fit into workplaces to changing the expectations and culture of companies to include women. We’ve worked with organizations around the world on changing behavior at scale, and what works with DE&I is what works with other strategic initiatives, from Six Sigma to safety. Our work and research indicate that treating DE&I like a strategic priority takes clarity of definition of each element of DE&I, linkage to business strategies and outcomes, committed leadership at every level, and systemic alignment with the rest of the organization to consistently put employees at the center.3

Still, because the CDO role is newer to executive leadership teams, it typically has had little resourcing, does not offer a well-developed career path, and isn’t the aspiration of many people. In fact, despite the complexity and the quickly evolving landscape, it is a role where many companies are content to promote someone from within who is simply from an underrepresented group and has passion for the topic. Taking this approach, however, is not the path to success; no other C-level role would be filled in this way. Moreover, it is also common that someone from an underrepresented group is chosen for this role because it helps to diversify the executive team. One central question emerges from all this: For any other role driving behavior change at scale by changing deep-seated beliefs, would any leadership team not have the person in that role control the levels to drive change—namely, people, budget, and processes? Though there has been some change in this respect during the intense period of the past two-plus years, it is still more common than not for CDOs to have to partner with others to get their agenda prioritized as part of any of those levers for change.

To be an effective leader in this new reality, a CDO needs to be adept at building strategies and tactics that fit into the business plan of the company; able to lead and influence without people thinking they are being judged, and, at the same time, to represent a point of view; entrepreneurial as they test and measure ideas as the space evolves; and focused on measurable results that can be known and/or felt by many. Again, this is much like the qualities of other successful executives who can drive sustainable change at scale.4 In line with this, many serious CEOs, CHROs, and CDOs have co-created strategies that are animated by, and aligned with, established business processes and, in many ways, support the business priorities and goals set by leadership.

Some companies have tried to address this complexity by appointing joint CHRO-CDOs—not co-leaders but one person holding both roles. But this approach ensures that a person who is already overloaded with pre-pandemic responsibilities, setting a hybrid work strategy, and meeting increasing employee expectations for companies to act with purpose and social responsibility has yet one more priority. We will explore elsewhere how CHROs can set priorities to ensure their own effectiveness, but to succeed with DE&I, companies need to appoint a dedicated leader. That said, the current focus on whether the CDO reports directly to the CEO is, we feel, missing the point. DE&I can only ever be just one of a CEO’s many priorities, and CDOs may not receive the access and support they need when they report directly to the head of the company. In our experience, having the CDO report to the CHRO ensures that the CHRO is also invested in the CDO’s success while ensuring the CDO’s voice gets heard at the most senior levels.

Finding the right CDO

Before embarking on hiring a CDO, the first step is for the CEO, alone or with the CHRO, to think very honestly about the following:

- How DE&I identifiably contributes to success of the core business strategy

- The variables of diversity that, over time, should be reflected to ensure those contributions

- Where the organization and leadership really stand on DE&I issues

- The leadership’s readiness for change and how fast they can drive change

- How they can do all of this while building on the established organizational culture, values, and language

In that context, we recommend that leaders consider the characteristics the CDO will need to deliver on the things that matter most to the company’s DE&I progress and what makes people successful with the company. Though the fundamental leadership capabilities for CDOs are the same as for most other leaders, where they have gained their experience and the types of roles they have previously held may be a bit different than that of other C-suite executives. In our experience, CDOs can combine any two—but not more—of the following types of experience:

- A public figure—often someone whose hire will make news and who benefits from relationships with constituencies such as the media, partners, or employees

- An executive whisperer—someone who will be able to generate the trust of most, if not all, of the leadership team; is sought out by them for help on DE&I, including in their own development; and can influence this group without the CEO and CHRO needing to step in

- An entrepreneur—someone who can start with a blank piece of paper and successfully launch a series of efforts

- A mechanic—someone who can come in and build out the basic functions and capabilities, often when a company already has a sense of what it wants to do

- A subject-matter expert—someone sought out when leaders are worried about getting things right and when a critical success variable is whether this person is seen this way by key internal audiences

- A role model—someone who represents and even embodies elements of the role that have significant meaning and relevance to key audiences; this can often overlap with other models (commonly the public figure, for instance)

Many people believe that certain types of diversity are particularly important in these roles. That isn’t wrong, given the importance of visible progress to core audiences and the role of representation in being able to recruit and retain the ideal team. But that doesn’t mean it’s the only consideration. Someone from a more dominant group who also cares deeply about DE&I and has significant experience driving change at scale could be a very good ally as a CDO. Now, we say this knowing that, from an optics perspective and a representation perspective—both of which are very serious—it may be hard for many companies to hire someone like this. Regardless of who is hired, too often, once a CDO comes in, leadership teams often mistakenly think that DE&I is now the sole responsibility of this person; when the person is from an underrepresented group, it even more often leads other members of the team to feel confident that they will take care of the company’s DE&I issues in a vacuum. This is not how leaders think about other strategic efforts. No one would put responsibility for success of a new cost-cutting initiative solely on the COO, for example, or a new marketing strategy solely on the CMO or technology adoption on the CIO.

To make it clear that the CDO has authority and the respect of the rest of the leadership team at all levels, we also recommend two other key considerations:

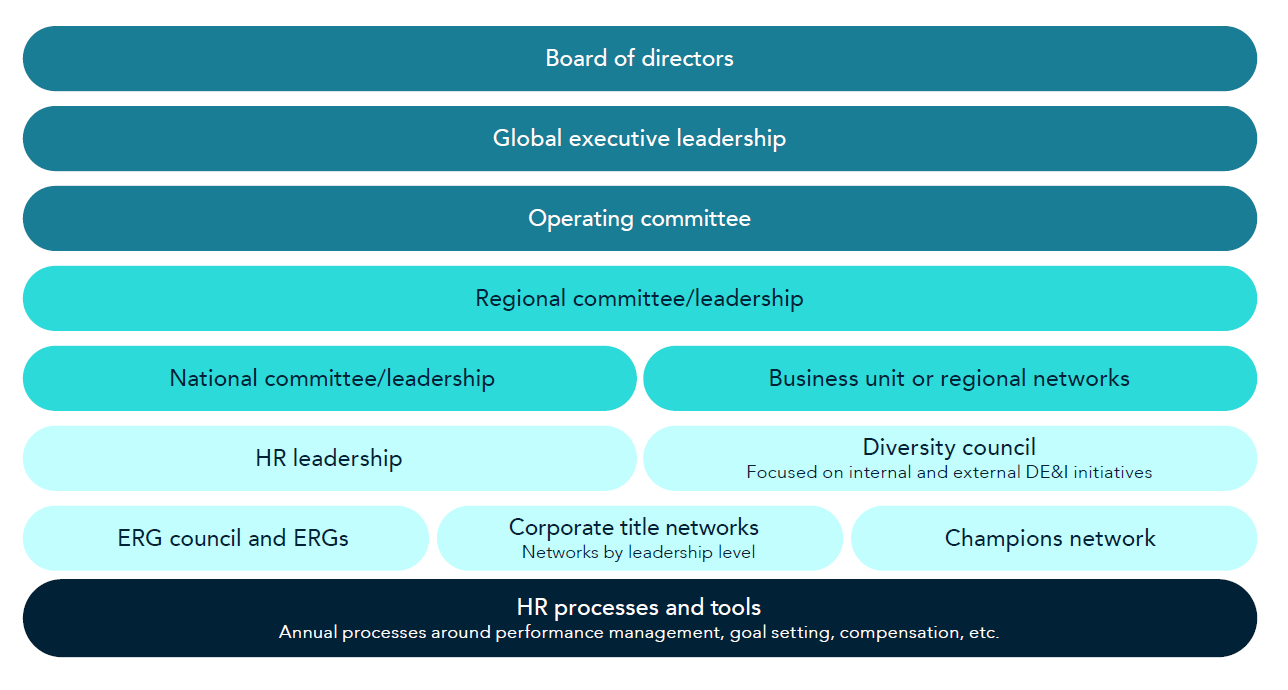

- The CDO’s remit should be expanded to go well beyond basic activities to support diversity so that they are positioned to at least start a conversation about an inclusive culture. Too often, the remit is focused on activities such as trainings, without ensuring that efforts to meet DE&I goals are part of a system to drive change over time. The details will vary from organization to organization, but, in general, CDOs need the right title, an effective governance model, control of their own budget, and an influential role in organization-wide decisions about people, budget, and HR processes. The CDO will need to be able to interact effectively with each of the levels of general corporate and DE&I specific leadership below.

- Honestly assess what is most needed for the company’s next steps and whether an internal or external candidate will be better to lead those steps. Finding a CDO internally brings value, such as that person knowing the culture and the organization, along with risks, particularly of that person being less able to drive meaningful change. So external candidates, such as a former CHRO from another company, or a consultant with significant transformation experience, may be better able to lead through change. We have seen some new CDOs with nontraditional profiles succeed in cases where corporate diversity efforts have been turbocharged because of crisis.

Our work and research suggest that companies leading the way on DE&I put employees at the center with clarity of definition, strategic purpose, leadership commitment and role modeling, and systemic alignment.5 Setting up the right person for success as CDO is a crucial element of these efforts.

About the authors

Lisa Baird (lbaird@heidrick.com) is the global managing partner of Heidrick & Struggles’ Human Resources Officers Practice; she is based in the New York and Stamford offices.

Jonathan McBride (jmcbride@heidrick.com) is the global managing partner of the Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Practice; he is based in the Los Angeles office.

References

1Jonathan McBride, Employees at the Center: What It Takes to Lead on DE&I Now, Heidrick & Struggles.

2Andrew Deichler, “DE&I Leadership Ranks Grow—Slowly,” Society for Human Resource Management, June 14, 2021.

3Jonathan McBride, Employees at the Center: What It Takes to Lead on DE&I Now, Heidrick & Struggles.

4TA Mitchell and Sharon Sands, “Future-ready leaders: Finding effective leaders who can grow with your company,” Heidrick & Struggles.

5For more on how leaders are thinking about this, see Jonathan McBride, Employees at the Center: What It Takes to Lead on DE&I Now, Heidrick & Struggles.