Inclusive Leadership

Securing the long-term gender balance in insurance

While many companies in the European insurance industry have improved their gender balance at the leadership level, that progress is unequal when looking at individual companies’ leadership, business units, and geographies. And for many organizations, there is a deeper concern that the pipeline of female leaders may be exhausted, with few women available for promotion between the middle management and executive levels. The implication is that the efforts the sector has made in addressing the gender imbalance so far might not be sufficient in the long run.

Many organizations are taking important steps to address the gap: gender balance issues and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) overall have become strategic considerations for leadership teams and boards; gender balance has been factored into succession planning; there are clear targets and metrics in place to measure success; and there is a vast array of policies such as equal pay, work flexibility, and parental leave that are being revised to remove gender inequities from working conditions. But still, many organizations feel that not enough progress has been made.

One of the main reasons for this lack of progress may be the way companies are framing gender balance in their organization; the more successful organizations are the ones that frame it as a business issue, not a women’s issue. “I think gender balance is an important business driver, not just a feel-good initiative you have to do,” said Paolo De Martin, former CEO of SCOR Global Life. “And it’s extremely important to go on a fact-finding mission to understand how your organization fares across geographies and divisions.”

So we went on a fact-finding mission to explore what the current landscape of gender balance in the European insurance industry looks like and to understand what some of the sector leaders do to make progress on this issue. We analyzed the gender balance at the top 30 European insurance companies and spoke to eight leaders about their approaches to shifting their organizations’ established systems and mindsets.

Overall, we found that while many companies are pouring resources into initiatives meant to support women’s career progression, not enough of them address another critical driver: culture. To attract, retain, and make the best of all talent in an organization, insurance companies must build inclusive cultures that make all employees feel that they belong and are being heard. For gender balance, that means addressing the challenges and barriers that may prevent women from maximizing their potential. The good news is that the leaders we talked to for this study represent some of the more progressive European insurance companies when it comes to DE&I and collectively shared ideas and best practice examples from their own repertoires.

No longer the only woman in the room (but still in the minority)

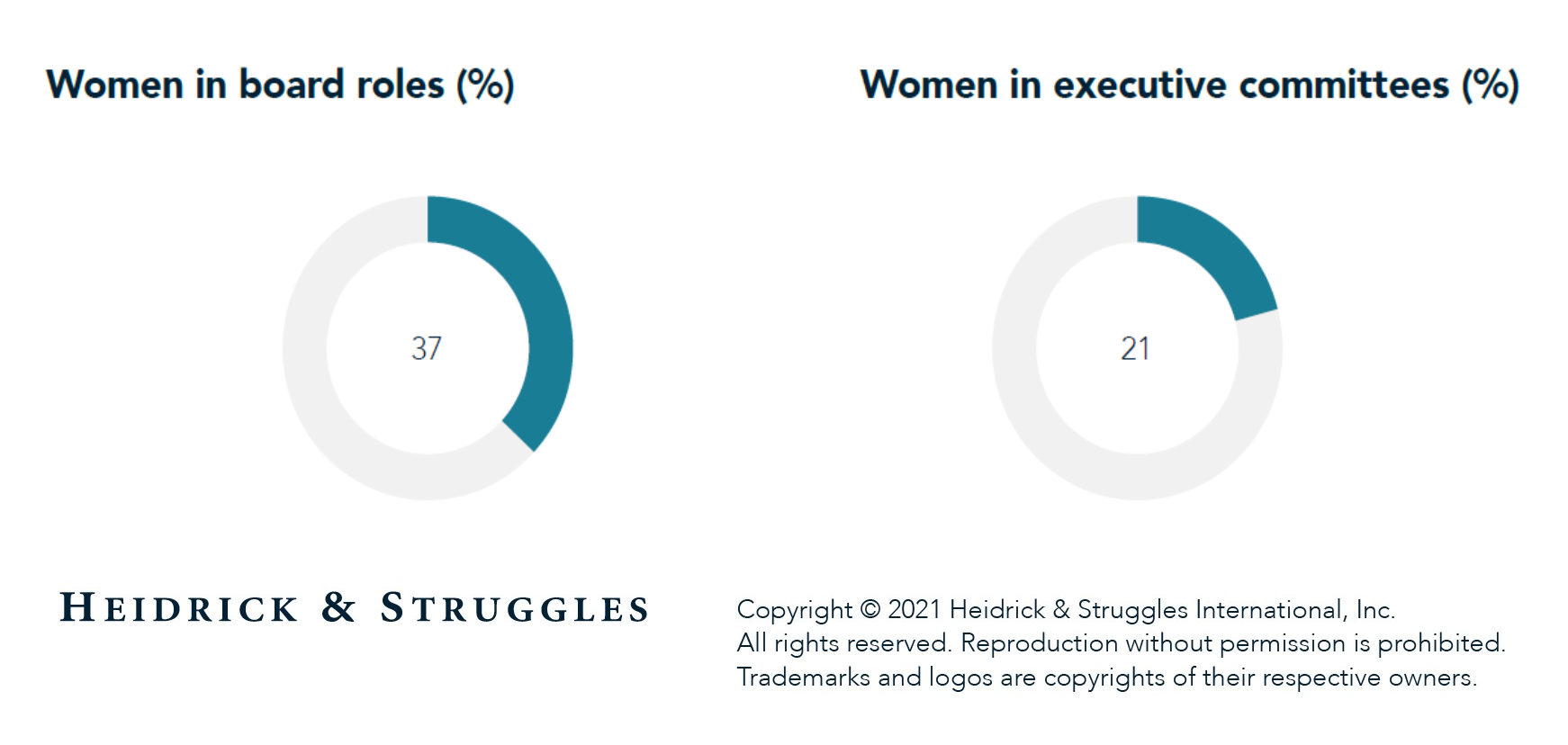

A series of regulatory measures in European countries and a growing awareness that an equitable gender balance positively impacts financial performance boosted attention and effort in insurance companies, particularly when it came to boardroom composition: our analysis shows that 37% of all boardroom positions in the top 30 European insurance companies are held by women.

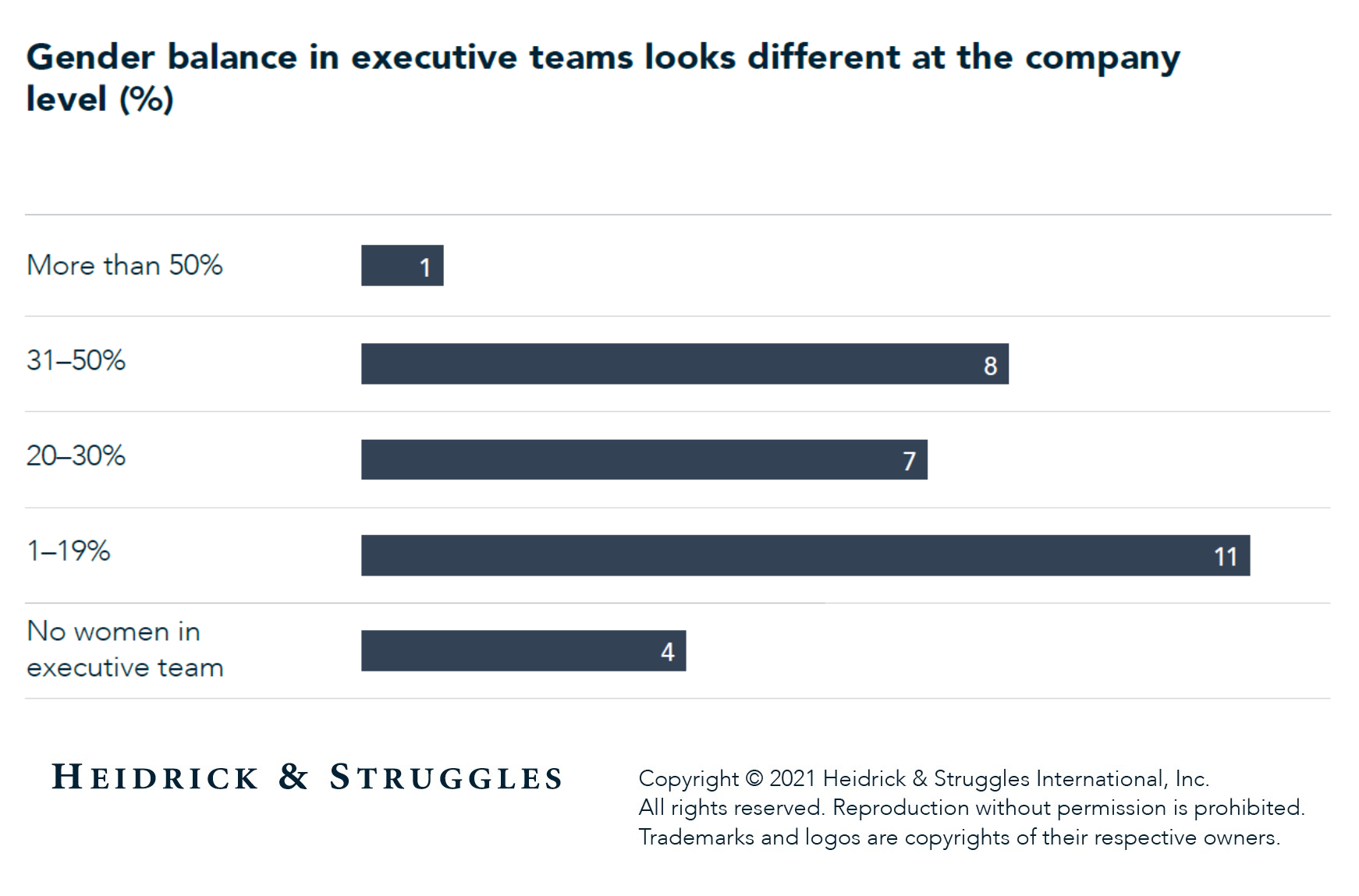

And while it is important to acknowledge the improving gender balance on boards, companies must turn their attention to the progress of women in executive positions, where the reality is starkly different: only 21% of leaders are women, across all companies. And that number masks huge variations: the proportion of executive team members who are women ranges from 0% to 53%. The extent of variations doesn’t stop there, with companies struggling for consistency across their operations. Jacqueline Hunt, strategic consultant to Group CEO at Allianz, said: “Progress in gender balance is being made unequally. We want consistency of experience around the group, but we struggle to reach the bare minimum in some places.”

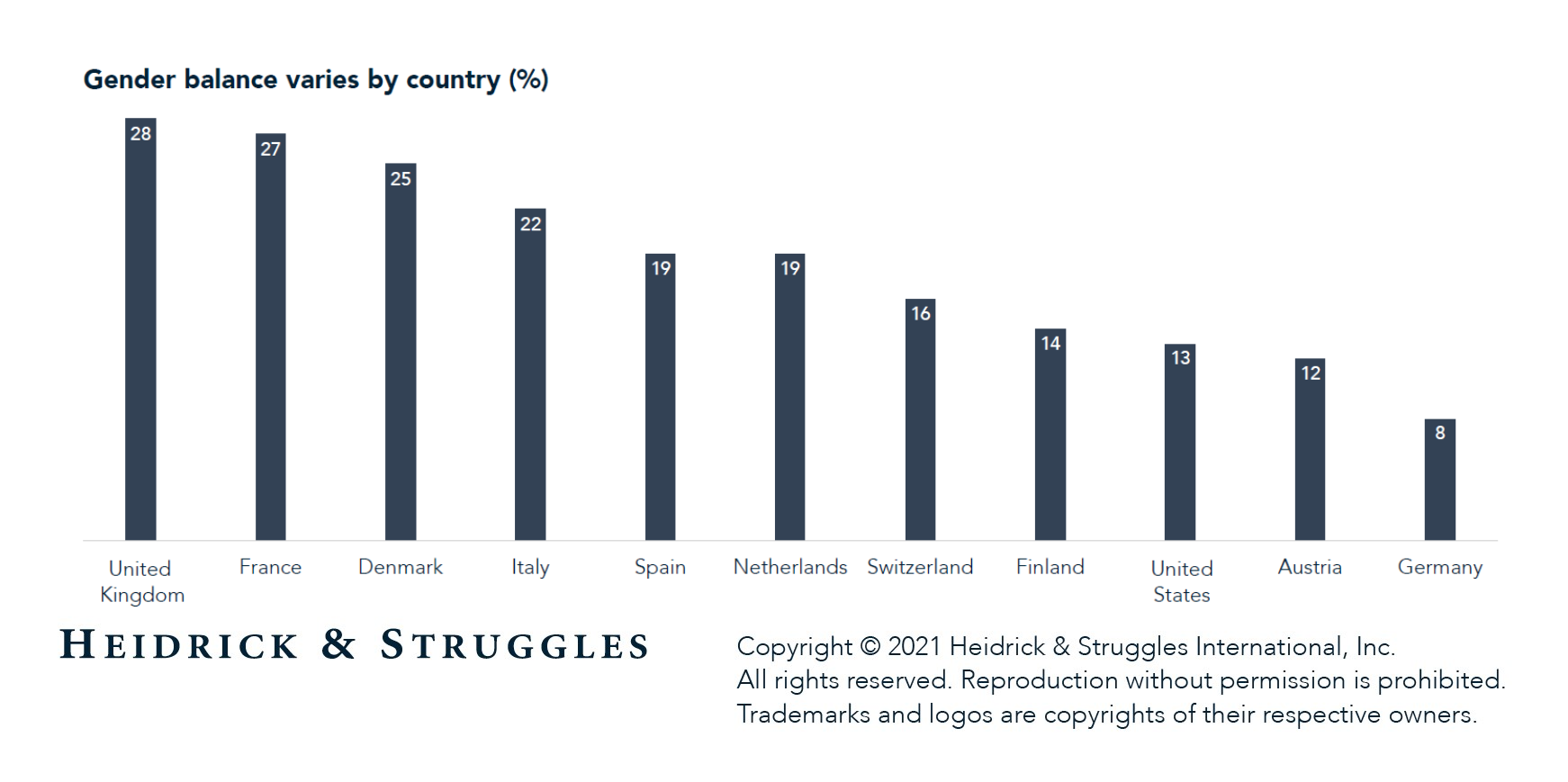

There are significant differences among countries, with the United Kingdom and France leading the way with just over a quarter of top seats held by women, and Germany lagging behind all European countries, with only 8%.1

Aside from a few exceptions, companies are not hitting the 30% critical mass that research indicates is necessary to make an impact.2 We found that 24 out of 30 companies in our study have less than 30% women in their executive teams, including 4 companies that have no women at all. And, in order to reach the 30% threshold, the leading European insurance companies would need 52 additional women executives—a 73% increase from the total women currently in leadership roles.

At first glance, there is a good balance when it comes to the proportion of roles with P&L responsibilities or staff roles, which generally is an indicator of the strengths of the pipeline for top jobs. For the companies in our study, out of the 76 women in executive teams, 42% have P&L roles and 58% have staff-line responsibility, which is a fairer balance than we see in our work across sectors. But, when we factor in the fact that women make up only 21% of leadership roles, the percentage of women with P&L responsibilities shrinks to 8% of total executive teams.

A fragile pipeline of women leaders

Executives hope that the progress made around gender balance is just the beginning. But this raises the question of how, and from where, more women will enter senior positions. “While there has been progress in gender balance in insurance, we are still in the early stages,” said Sian Fisher, CEO at the Chartered Insurance Institute. The question of how to manage the career progression of women within the sector is still a big question mark.”

Internal candidates are the main source of female leadership now: only 31% of women in executive teams were hired externally. And many internal promotions seem to have been the result of specific, targeted efforts rather than a long-term approach to address the gender balance for many organizations. In light of this, many executives have raised concerns about the sustainability of gender balance in their internal pipeline, noting that the level below the C-suite is almost exhausted in terms of female talent. “Like many companies, we have an isolated lagoon of women at the top,” said Sian Fisher, CEO at the Chartered Insurance Institute. Kate Markham, CEO of Hiscox London Market, added, “We have areas of great gender diversity, but when you peel away one layer, it is not always consistent across the organization for a variety of reasons. That’s a problem because promoting female talent requires there to be a breadth of gender-diverse talent underneath them, ready to step up, so that’s where our focus is at the moment.”

“We’ve struggled, as others do,” said Allianz’s Hunt. “Our middle management and below are 52% female, but at the in-between levels, we do lose a lot of women. Therefore, many of our external hires are women, and the board is focusing on a better gender balance for leadership succession.”

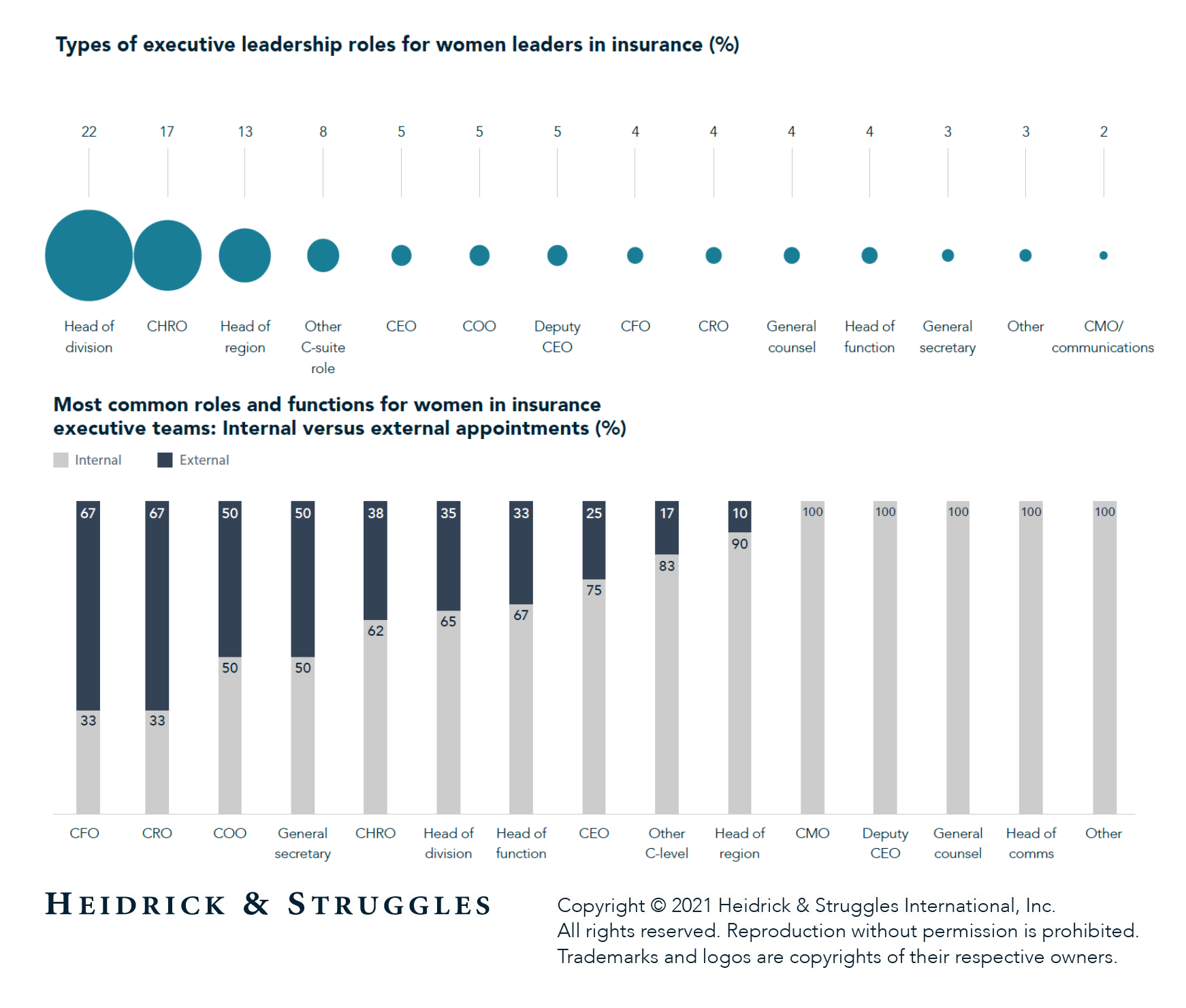

Data suggests that while the most common role for the female leaders in our study is head of a division, overall, it is far more prevalent to find women, both internally and externally, in skilled staff roles such as HR, legal, or operations. But the interesting insight comes when looking at how women leaders are appointed: a large proportion of C-suite positions (CFO, CHRO, COO, or CRO) are external hires, while the majority of staff leadership roles (head of communications, general counsel, deputy CEO) have been promoted internally. Looking even closer at the four female CEOs in our study, while only one was hired externally for the top role, two others joined their companies in their previous positions and did not rise through the ranks internally.

Making the best of all available talent: Strategically increasing representation

To ensure a sustainable gender balance for the long term, leaders need to better understand how and where within their companies women are currently underrepresented, struggling to influence business decisions in critical areas, or unable to experiment with tools to increase the gender balance.

A potential starting point for progress is to assess the size and composition of the executive leadership team in order to understand whether it is still fit for purpose and future proof. Research shows that many board directors and CEOs think that the current format of the top role needs overhauling in order to keep up with the changes in business and operational models; future-proofing executive teams requires flattening hierarchies and a broader set of skill sets.3 Considering only the 30 companies in our study, we found that they have leadership teams of wildly different sizes, from 4 to 26 executives, reflecting different philosophies of management around what constitutes a C-suite role. It is likely that while some insurance companies have undergone a systematic review of how the current roles and dynamics in the leadership team are fit to steer their organizations toward their goals, many others still have legacy formats that would benefit from a shake-up.

While adding roles to the C-suite doesn’t automatically lead to a more equitable gender balance, it will tip the scales. Smaller teams are less likely to include the leadership roles women more often hold, such as CHRO, legal and compliance, marketing, or even general management positions that include heads of regions or divisions.4 This seems the case for the European insurance companies in our study as well, which makes the case for a deeper look into how their leadership teams are structured and how they operate. Penny James, CEO of Direct Line Group, pointed out, “At the senior level, you have to choose your moments to address gender balance, to make sure it’s conscious and impactful. That means not looking at each move individually but considering your executive team broadly. If you need more roles to play with, broaden the executive committee thoughtfully to make sure you’re adding a different skill set. On occasion, I’ve added a role to the executive committee for a spell to give someone experience. You need a bit of creativity at times.”

Because the faltering pipeline is one of the key obstacles for improving the gender balance, succession planning must be a priority for insurance companies. They must understand what their strengths and weaknesses are and make plans for how to address pain points, making detailed plans a few levels down into the organization and mapping talent both internally and externally, going beyond sector boundaries. Hiscox London Market’s Markham shared that they have decided to look at areas where they have few women, such as class underwriters, and then identify and hire talented young women at the junior and medium management levels to promote internally. “Some say that the talent is not there, but that’s just an excuse. The talent is out there. You just have to find them. And when you get them, keep them happy and thriving so they never want to leave again,” she said.

Diverse succession planning seems to be even more pressing when it comes to roles with operational or technical skill sets such as underwriting, statistics, actuaries, AI and data analytics, technology, and claims. The internal pipeline of women with these skills is particularly thin, and some leaders point out that there are few women, even outside the sector, with these transferable skills. “In the data space, traditionally a male-dominated area, we have a few women, but not a rich pool. It is a critical area for our future,” said Alison Martin, CEO EMEA and Bank Distribution for Zurich Insurance Group. The specific scope of data analytics application in insurance requires a hybrid skillset that combines underwriting with data science, and the individuals with this skillset are so rare that they are being considered “purple squirrels.”5 As a large body of research indicates that the talent gap in data analytics is sure to increase in the future across sectors and the battle for top talent will heat up, insurance companies should plan how to attract and reskill people for areas that combine data science and artificial intelligence with underwriting or actuarial experience. That could mean a different approach for finding and developing talent, including working with educational institutions to develop more tailored courses and prepare more students for these roles earlier on and offering more technical apprenticeships to a more diverse pool of people. Overall, it requires a more proactive, thoughtful approach, as trying to hire a purple squirrel at the exact time when a company requires his or her specific skill set might prove challenging.

For succession planning, companies must also make sure that there is balance when it comes to the people involved in the selection process. “Interview panels [should be] very diverse and ensure there is opportunity to talk to multiple women during the selection process,” said SCOR Global Life’s De Martin.

Talanx Group has opted for an organic growth approach to strengthening the female pipeline: “We are working toward building that base internally through organic growth,” said Torsten Leue, CEO of Talanx Group. “I know it takes more time, but it’s worth it.”

Retaining women on the leadership track seems to be a common challenge for European insurance companies, particularly when it comes to one or two levels below the executive team. Many insurance companies we talked to are looking at equal pay for equivalent work: for example, Zurich Insurance Group reviews employees’ salary annually to ensure that gender is not a factor when it comes to salary decisions, and therefore not a trigger for their departure.

Parental leave and childcare are other critical issues companies are looking at. “When you lose so much talent and you know that women tend to leave the company around the maternity experience, you have to ask what you can do to protect their career paths," said SCOR Global Life’s De Martin. Indeed, companies must assess their policies and attitudes around motherhood in order to reduce attrition of their female leader pipeline. Some insurance companies have been focusing on making parental leave equitable and attractive by raising their game both in terms of the actual paid leave on offer and in opening it up to all parents regardless of gender. In Australia, Zurich Insurance Group went even further, extending leave for all circumstances related to birth, including in vitro fertilization, surrogacy, adoption, miscarriage, and stillbirth. It is also addressing a less talked-about issue: the gap in pension contribution on unpaid leave that reduces retirement savings. The company is working to make sure that women can make sufficient contributions to bridge the gap.

Building inclusive cultures to sustain gender balance

Focusing on parental benefits, flexible working, women’s networks and events, and sponsorship programs goes a long way to supporting women in the workplace. But the best approach to balance gender representation in a sustainable way entails tackling a more nebulous goal: building and nurturing inclusive cultures where all employees feel that they belong. (For more, see “Creating an inclusive culture: Five principles to create significant and sustainable progress.”) Allianz’s Hunt said, “As a culture, you need to accept that it’s going to be uncomfortable at times. Gender balance and inclusiveness, in general, is not just about numbers and quotas. It’s a fundamental cultural change.”

To attract and retain women, companies would be wise to evolve their culture with a strategic agenda that is purpose driven and human centric. Zurich Insurance Group’s Martin, for example, shared how the company’s culture has moved from one very focused on technical excellence to one that is more customer focused, forward thinking, and caring. “These are values and behaviors that you would naturally associate with gender balance,” she said. “The cultural shift is changing how we think about and value inclusion, as well as what actions and policies are consistent with those values.” She also pointed out that the cultural journey toward inclusiveness is influenced by the gender balance and that a more inclusive culture will attract more women: “Sometimes our culture changed because of us having gender diversity, but quite often, it’s the other way around. I think they are interlinked.”

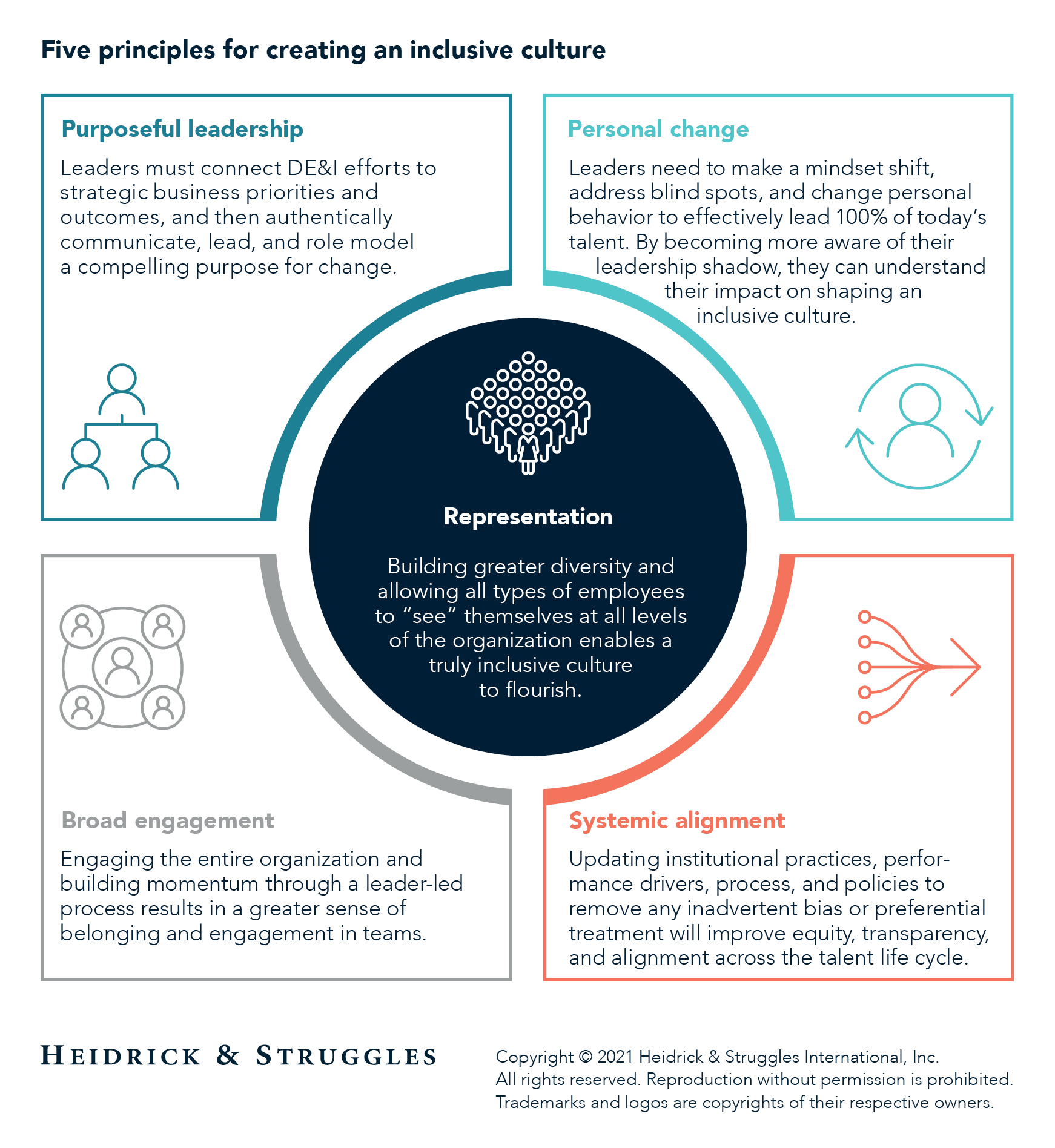

So, how can insurance companies build and nurture inclusive cultures? Over the past four decades of helping companies with their culture shaping, Heidrick & Struggles has identified five core principles required to shape sustainable, high-performing cultures: purposeful leadership, personal change, broad engagement, systemic alignment, and representation. These principles may also be applied to improving representation. As we addressed representation in the previous section, we will now turn our attention to the other four principles.

Purposeful leadership

What leaders say and do sets the tone and strength of inclusion in any organization. It is difficult to overstate the extent of the CEO’s influence over diversity and inclusion. The CEO has a say in who gets promoted, whose opinions are valued, group dynamics, and who gets tapped to lead and sponsor initiatives. The CEO can demonstrate to his or her organization how important inclusion is and to what extent the gender balance is valued. “If the CEO is not on board [with diversity and inclusion goals], it will be just incremental change and not a big transformation,” said SCOR Global Life’s De Martin. “Diversity and inclusivity drive better decision making. Discussions are deeper and more complete when you have balanced genders in the room,” De Martin continued. “There’s a higher level of intensity and different perspectives. If only men are in a meeting, I gently make sure there is female representation in the next meeting—otherwise, I am not making a decision.”

But the most important contribution to the gender balance a CEO can make is to reframe the narrative around it as a business issue, not just a women’s issue, and to make it a priority. CEOs are the most visible role models and champions, capable of speaking up for women and acting as a sounding board for them in difficult situations. “It's important that role models know how to communicate and tell the story of what they are doing right, even if what they say can be controversial. It takes courage and also the ability to tread a fine line, strengthening the culture rather than killing it,” said Talanx Group’s Leue.

Being approachable and available to a variety of people in the organization is also a common theme we heard from the leaders we spoke to in our interviews. Allianz’s Hunt, for example, is a big proponent of mentorship programs for women. “I have spent 25 years mentoring women. Most of them are in significant roles now,” she said.

Personal change

Consciously or not, many organizations still have double standards for men and women. A common example is gendered views on the types of roles that are appropriate for men or women: “I still spend some of my time discussing and dispelling biases around what women can and cannot do, either in a functional role or in particular geographies,” said Allianz’s Hunt.

In order to be effective inclusive leaders, senior executives need to explore their own biases and blind spots and shift their mindset, and then determine how they can influence the way in which their companies create and maintain a sense of belonging and inclusiveness. That means actively looking to identify and address any harmful perceptions, both personally and at the organizational level. For instance, many view diversity initiatives as at odds with a meritocracy, be it in organizations or cultures. But Zurich Insurance Group’s Martin described a mindset change that made her look at the issue in a different way: “Initially in my career, I didn’t see a problem with gender diversity, as I believed in meritocracy; it was only later in my career that I realized I got a lot of help from people who championed me, to the point of putting their own careers on the line. It humbled me and taught me to pay more attention to people who might not have senior sponsors but are equally talented.”

Importantly, many of the executives we spoke with highlighted that their DE&I journey encompassed more than gender. Direct Line’s James argued that diversity initiatives shouldn’t stop with gender but should encompass other identities and characteristics: “You can’t do gender on its own,” she said. “You either have a culture that is accepting of people’s differences, or you don’t.” Leue agreed: “For me, diversity does not stop at the gender question but also includes factors such as internationality.”

Broad engagement

Gender balance isn’t an issue for women to advocate for on their own. It should be viewed within the bigger picture of organizational transformation and the goal of creating a sense of belonging for all and knowing how to bring people along on the journey. It’s also important to carefully craft the persuasive narrative for and with the men in the organization to make sure they are on board with and equally champion the cause. That can require making space for uncomfortable but necessary conversations. Hiscox London Market’s Markham said, “It’s also very important to watch out for how men feel, as women don’t welcome the perception that they deserve special treatment. To address that misconception, you must think about both men and women in your organization, take them all on the journey, and make everyone allies and champions. This is something we’ve done through our Women at Hiscox employee network, which set a goal to get more men involved and has seen more men actively participating in the last two years as a result of this.”

“Transparency and buy-in is needed to avoid tension,” advised Talanx Group’s Leue. “An inclusive company will make sure that the reasons behind any gender balance efforts are communicated clearly to avoid backlash.” Direct Line Group’s James shared that she has a Q&A every month to which all 10,000 staff members are invited and can ask her any questions they like, including on diversity and inclusion issues. “It is sometimes daunting, as the questions can be very tough to deal with,” she admitted, “but you have to be brave and do this.”

At Allianz, the local women’s network evolved into Allianz Neo, an employee network that looks at gender balance, inclusion, and equality. The network emphasizes that achieving gender balance is not only an area where women stand to gain. Men need to be part of the journey as well and will also benefit from gender equality.

From our experience in working on issues related to diversity and inclusion, the most effective approaches need to include ways in which leaders and employees who are not part of a minority group can experience what it means to be part of such a minority at an emotional level, in order to build empathy and compassion. For example, some companies have started experimenting with carefully crafted virtual tools that allow anyone to live the experiences of a woman or racial or ethnic minority in the workplace to give them a sense of the barriers and challenges they face.

Systemic alignment

Zurich Insurance Group’s Martin recalls when only 20% of the company’s applicant pool in the United Kingdom was women. But after it added more flexibility to the job posting and used gender-neutral language, the company saw a 40% increase in women applicants. “It was so simple, and we ended up with better gender diversity across business functions,” she said.

The use of inclusive, gender-neutral language should be reinforced throughout companies’ policies, in areas such as benefits and employee communications. Today, advocacy for gender-neutral and inclusive language is primarily on behalf of the gender-queer and disabled communities, but it has proven to be effective in promoting a fairer gender balance overall. To assist them in this mindset shift, companies can employ data-analysis language platforms that can assess in real time all content to identify to what extent a job posting, policy, or speech is inclusive.

The effective use of inclusive language is one tool at a company’s disposal. But systemic alignment means embedding inclusion in processes, policies, systems, and day-to-day business operations—both in HR and beyond. That implies a thorough assessment of the key HR points—including hiring, performance management, assessment, promotion, and reward—and using disaggregated data to understand how various demographic groups fare through the different stages of employee experience. This will allow companies to understand where representation falters and what some of the causes are.

Beyond HR processes, SCOR Global Life’s De Martin made a direct connection between increased diverse representation and product development and innovation: “Learning to see the world through multiple lenses—particularly gender and race, and the challenges that often restrict various groups—can change the way companies think about their products and the way they do business. We now ask, ‘Are our products reaching the communities that need life insurance? Maybe they are too expensive or just not right. How can we extend the product reach?’”

Measuring progress on gender balance

“One of the most important factors of success with gender balance is how you measure it,” said Hiscox London Market’s Markham. “When we set our metrics, we included business unit CEOs and functional leaders in the process. We set goals around different aspects of the career life-cycle—this included a focus on gender-balanced promotions, succession planning, and recruitment shortlists. Each business has slightly different metrics and plans based on its starting point and its specific challenges, but getting that engagement and buy-in from the start was vital.”

“We are an analytical and engineered-minded business,” said Allianz’s Hunt. “That means a large number of KPIs [key performance indicators], including percentage of personnel group through various businesses, new promotions, compensation, and attendance of training courses. These are very active KPIs that we monitor and hold ourselves accountable for.”

Currently, compliance reporting and engagement surveys are the most popular method for tracking progress on gender diversity. Talanx Group’s Leue, for example, said that Talanx Group issues its survey as part of its annual health check and benchmarks the company against its peers. And, at the Chartered Insurance Institute, Fisher said, they have a quarterly survey to measure progress, but added that surveys should be combined with hard data: “HR metrics related to DE&I are critical in not only measuring progress but also making it happen. CHROs need facts and figures to convince their stakeholders of how DE&I fits into the analytical approach of a business. The lack of data in the narrative is a massive risk.”

A more controversial metric for tracking progress on gender diversity is its link to executive compensation. Insurance companies have taken a mixed approached. Some of the executives we spoke with believe that results speak for themselves and that adding a DE&I dimension to executive pay is not necessary, while others see it as an important component in building inclusive cultures. Direct Line’s James said, “We have added both financial metrics and people metrics into the pot, with the people metrics primarily focused on gender diversity at the moment. It helps us have a healthy debate of the long-term sustainability.” For AXA, another leading European insurance company, diversity in teams, and gender balance in particular, is a shared goal for the leadership team and the CEOs of the company’s different businesses. And, beyond numbers, simple visibility of women in leadership roles is another important way to measure progress.

Whatever the organization’s means of measuring its gender balance and DE&I, leaders should be cautious of how they define success. Direct Line Group’s James cautions that “the CEO should define what ‘best’ looks like. And ‘best’ is not replacing the previous man with a woman to do the same job, in the same way—you will fail. And a CEO must think holistically about the team, not just about the most obvious fit for the role.” And the way companies define and measure success should be clearly communicated within and outside the organization. “Transparency is important to make sure everyone understands how diversity contributes to the success of the business and how it helps companies make better decisions,” said Talanx Group’s Leue.

About the authors

Jenni Hibbert (jhibbert@heidrick.com) is a partner in Heidrick & Struggles’ London office and the global managing partner and head of Search Go-To-Market.

Wolfgang Schmidt-Soelch (wschmidtsoelch@heidrick.com) is a partner in the Zurich office and the regional managing partner of the Financial Services Practice for Europe & Africa; he is also a member of the CEO & Board Practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the following executives, Paolo De Martin, Former CEO, SCOR Global Life; Sian Fisher, CEO, Chartered Insurance Institute; Jacqueline Hunt, Strategic Consultant to Group CEO, Allianz; Penny James, CEO, Direct Line Group; Torsten Leue, CEO, Talanx Group; Kate Markham, CEO, Hiscox London Market; and Alison Martin, CEO EMEA and Bank Distribution, Zurich Insurance Group, for sharing their insights for this article. Their views are personal and do not necessarily represent those of the companies they are affiliated with.

The authors also wish to thank Priya Dixit Vyas, Jennifer Flock, and Konstantinos Balasis for their contributions to this article.

References

1 The situation in Germany could, however, change in the next few years, as new laws have been recently introduced to allow women on management boards to suspend their liability while on maternity leave and not be forced to resign to avoid it; the German parliament also plans to introduce gender quotas at the largest 70 companies in the country.

2 Jasmin Joecks, Kerstin Pull, and Karin Vetter, “Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm performance: What exactly constitutes a ‘critical mass’?” Journal of Business Ethics, Volume 118, Number 1, November 2013, pp. 61–72.

3 John de Yonge, “Has your C-suite changed to reflect the changing times?” EY, September 24, 2019.

4 David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan, “Diversity in the C-suite: The dismal state of diversity among Fortune 100 senior executives,” Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, Stanford Closer Look Series, April 1, 2020.

5 Sooraj Shah, “Rise of the data scientist in insurance,” Raconteur, April 26, 2018.