Private Equity

Closing the leadership gap in private equity: Practical steps private equity firms should take now to strengthen their portfolio company leadership

Executive leadership is increasingly important for private-equity-owned companies and the firms that invest in them. When private equity (PE) firm executives list their priorities for value creation, they put leadership first, and by a big margin: They cite it 60% more often than efficiency or growth, and 90% more often than strategies such as bolt-on acquisitions.1

It is important to understand why leadership matters so much—and so much more than it once did—because the “why” reveals the “what next”: the agenda for action. Our research and client experience tell us there are three reasons leadership’s importance has grown. The first reason is steadily lengthening intervals between a PE firm’s acquisition of a company and its eventual sale to another owner. The median holding period is now six years, according to PitchBook, which is double what it was at the beginning of the century. That means more time during which value must be created not through financing but operationally—by making things, advising clients, satisfying customers, and managing people.

Second, today’s portfolio company executives need a broader and deeper set of skills than their predecessors—conspicuously, including that of forming and developing leadership teams. These days, most PE deals are add-ons or roll-ups—by some estimates more than 70%, more than double what it was just a few years ago. These require integrating C-suites, reimagining and restructuring portfolios, and, often, transforming departments that ably supported a middle-market business into functions capable of serving international enterprises many times larger.

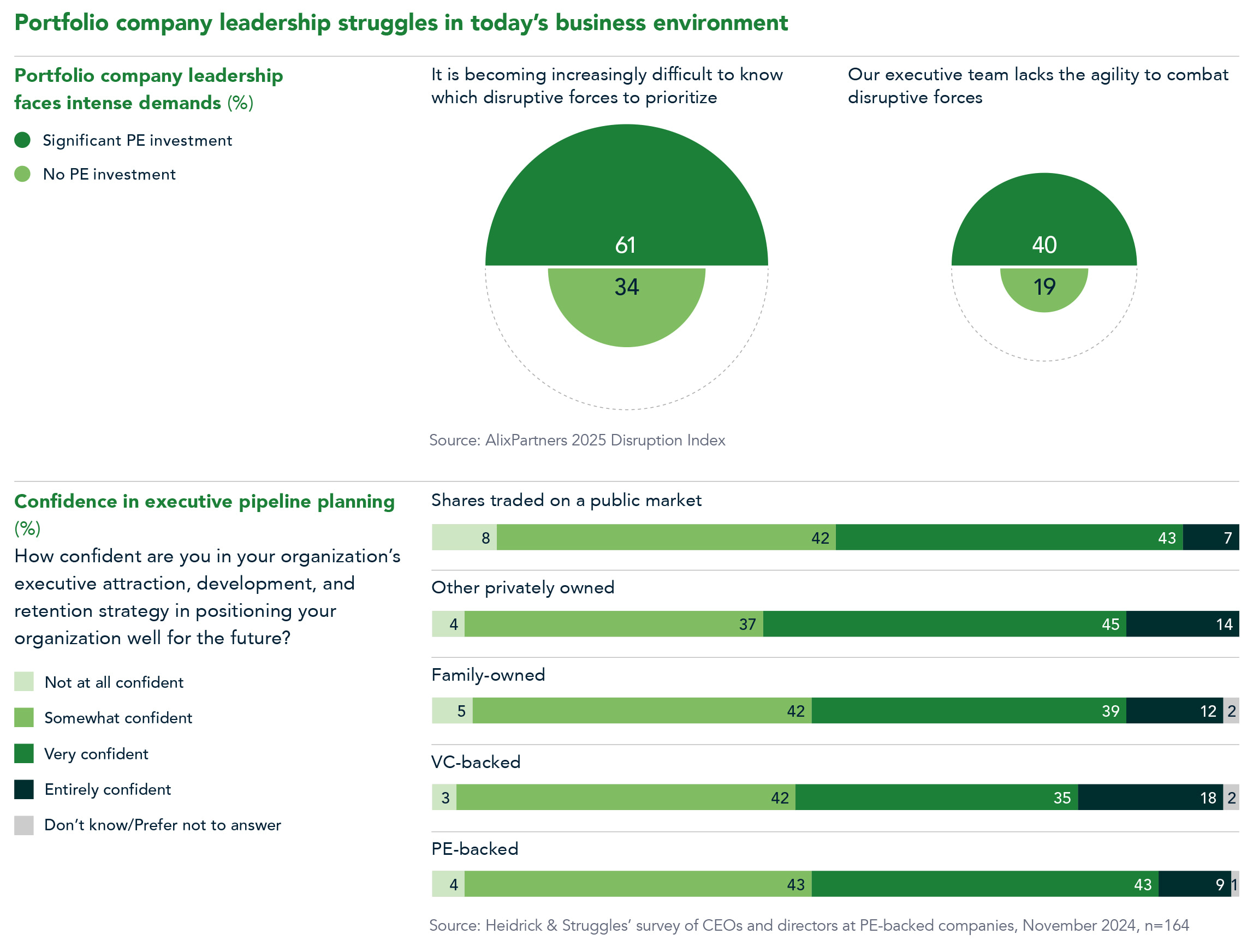

Third, the business environment itself is much more challenging, with multiple, simultaneous disruptions—from tariffs to technology—creating what some have called a “polycrisis.” Among companies of all kinds, leaders say the most significant challenges they face are economic and geopolitical uncertainty, and among those who are concerned with these issues, only about a third are confident their organization can manage them.2 CEOs and directors at PE-backed companies have a slightly different mix of concerns and, in some cases, even less confidence in the effectiveness of the executive team to manage them.

Indeed, a startling 41% of PE executives told us that senior portfolio company leadership—its quality, retention, and continuity—will be a significant challenge in the year ahead.3 In another survey, nearly half of PE board members and CEOs said they did not have much confidence that their executive pipeline strategy was positioning the organization well for the future.4

Opportunities for improvement

What, then, should PE firms do to ensure that they have the best possible portfolio company leadership, not just at the start but also throughout the holding period? How should they identify what they need and evaluate whom they have? How should they motivate and support—or challenge and change—the team as circumstances and strategies require? From research conducted by both our firms, and experience from working with scores of PE firms and hundreds of portfolio companies, we have identified three opportunities.

Create a robust process for hiring and assessing senior talent

Public corporations bring in a new CEO every seven years or so, our data shows; a decent-sized PE firm will hire that many CEOs every year. So, it should have an effective process in place for doing so. It should have a playbook, know what works, and have experts on staff or on hand who are familiar with the firm and have relevant industry and PE experience. Advanced PE firms have made significant progress in this area. Today, a majority employ a human capital partner, or someone with an equivalent title, whose job it is to oversee how portfolio company executives are hired and assessed. Virtually all PE firms (97%) say they use external interviewers or formal assessments to evaluate CEOs, up from 61% in 2018.5

That said, the approach and focus of human capital partners are varied. Some have little operating authority in their firm. Some primarily orchestrate the administration of psychological assessments, rather than managing a full recruitment process. Many are involved in CEO, CFO, and board appointments but do not have the bandwidth to pay attention to broader C-suite leadership. Some are engaged during acquisition, due diligence, and onboarding but take a back seat to operating partners thereafter.

And the existence of a reliable process remains stark. Only about a third of leaders at PE-backed companies report that discussions about CEO or director succession are expected, encouraged, and pursued on an ongoing basis.6 This is about half of the proportion of leaders at public companies who say the same.7 Yet there is a high and growing likelihood that a portfolio company will need a new CEO during the holding period. Heidrick & Struggles data shows that over 70% of CEOs at PE-backed companies are replaced during the average holding period, while AlixPartners data reveals that most CEO turnover—55%—is unplanned; that is, at the instigation of the investors or the CEO.8

Because choosing the right executives is vital and ongoing, PE firms need a repeatable process. This process should enable them to institutionalize knowledge and learn from their mistakes and successes, and it should give them the ability to see talent across the portfolio. And it should include measurements of success, so that areas can be targeted for improvement. We know of many PE firms that excel in some of these areas, but none that excel in all.

Ensure leadership stays aligned as the business evolves

As market dynamics shift, roll-up strategies change, and holding periods extend, PE firms face a crucial challenge: ensuring portfolio company leaders remain aligned with the investment thesis while it evolves and while leaders themselves are also growing into expanded roles. Strategy pivots are almost inevitable during extended holding periods. In addition, the scale and complexity of portfolio companies often increase dramatically, particularly for roll-ups. This means CEOs and their teams are not just running larger businesses but also integrating multiple management teams, navigating cultural alignment, and managing new operational challenges.

PE firms therefore need to know whether the current leadership team can deliver the revised outcomes. Even if the answer is yes, leadership might need to be reinvigorated, realigned, and re-equipped for what’s ahead. When things start to go off the rails, PE firms tend to bombard the company with requests for information and analysis so they can figure out the bigger picture of options, while the management teams quite often are embroiled in day-to-day, tactical activities. It’s important for both parties to step back and realign.

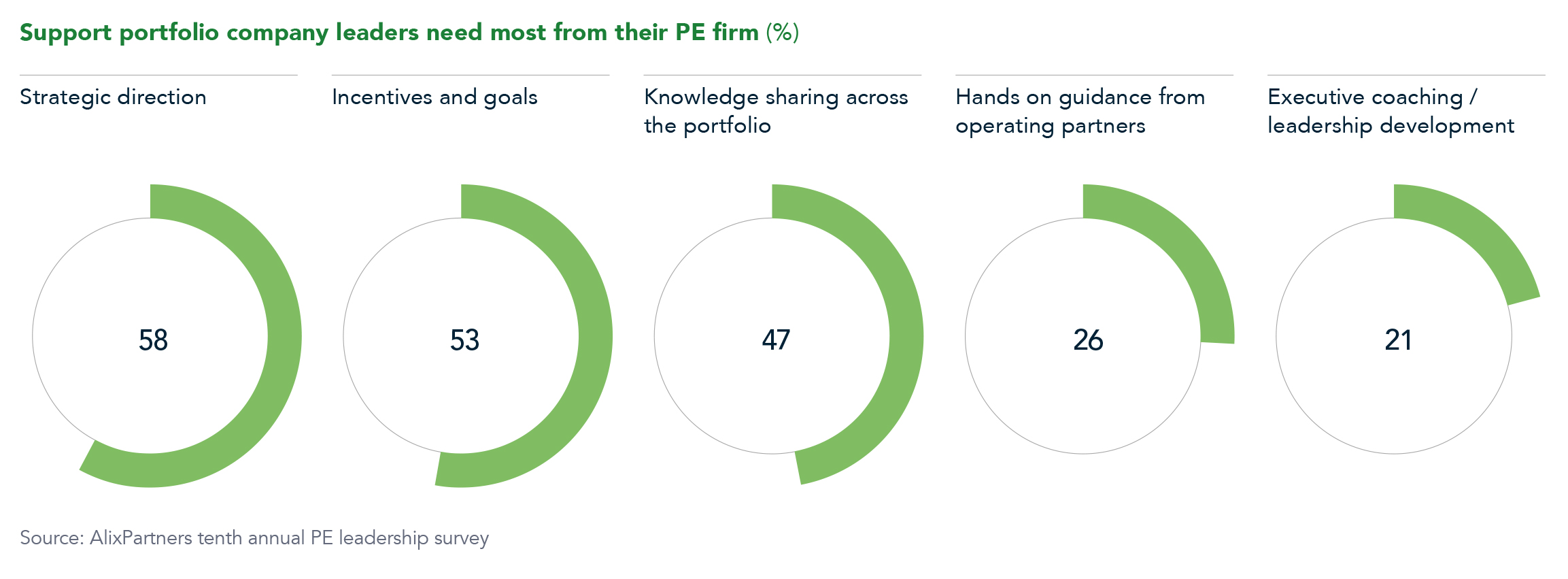

That realignment should include examining incentives. If incentives are too tightly tied to the initial deal thesis, they can produce a “frozen” leadership team, unwilling to adapt to changed circumstances. Contrast this with publicly traded corporations, where senior leaders far more often rotate roles, take on new responsibilities, and bring fresh perspectives. PE firms should consider how to inject similar flexibility and evolution into their portfolio leadership teams, because even the best leadership teams can stagnate or veer off course if their incentives and priorities aren’t aligned with the evolving investment thesis. Indeed, when portfolio company leaders are asked what support they need most from investors, they cite incentives and goals twice as often as hands-on coaching or development.

Help portfolio company leaders build their teams and bench strength

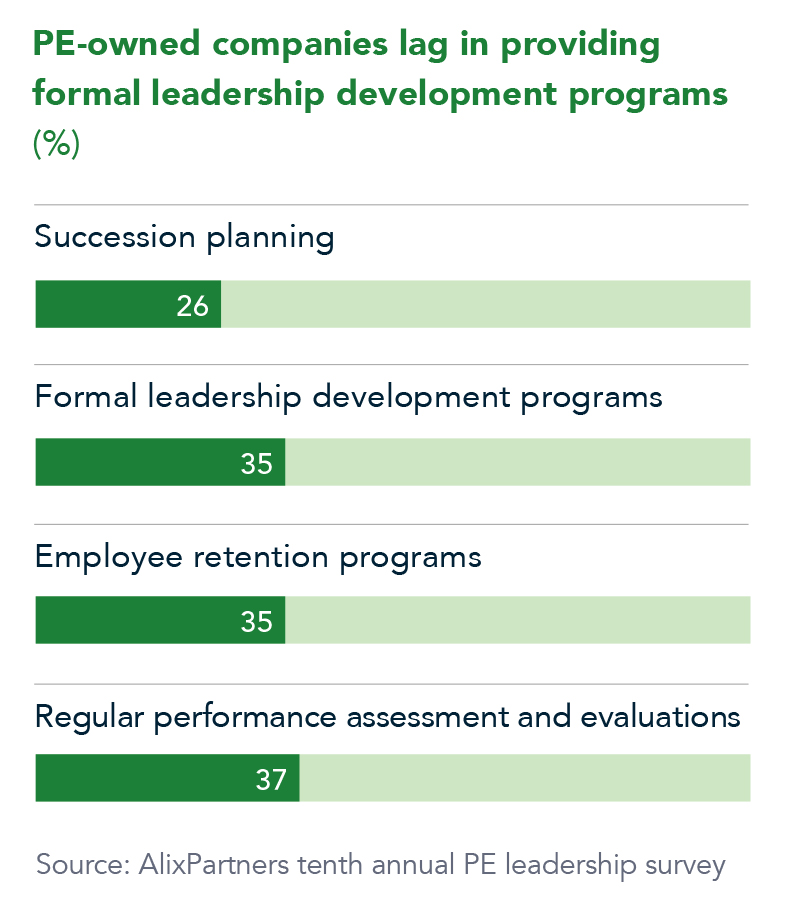

What goes for senior leaders also goes for those deep in the organization: succession planning, high-potential programs, and other talent development initiatives are far too rare in the industry. These mattered less when holding periods were just a dozen or 20 quarters long. Fewer than two in five portfolio companies perform regular performance assessments, and only a quarter have succession planning programs. In a recent Heidrick & Struggles survey, only 16% of CEOs and board members from PE-backed companies said that CEO succession planning is among their top priorities and treated as such. As AlixPartners’ Ted Bililies wrote in Harvard Business Review, “For old-school PE firms, talent management is an afterthought.”

It is not a PE firm’s job to run portfolio companies’ talent programs, but it should be the PE firm’s responsibility to insist that portfolio companies invest in talent. That can be new territory for portfolio companies. Their HR departments are often thin to the point of being skeletal. The HR teams at midmarket and founder-led companies often limit themselves to transactional personnel matters. Boards may not be able to help: Because most PE portfolio companies’ boards tend to be comprised of investment professionals and people with sector expertise, they can be lacking in directors who have experience with CEO or executive succession planning. Companies may need outside help. And they need to ensure that their talent investments are producing top- and bottom-line results.

It can also be new territory for PE firms. They are and should be lean organizations, focused on finding, making, and managing acquisitions; adding value to the businesses they acquire; and then leading successful exits. Capital has historically been their focus, but today, human capital matters as much as financial capital. Adding operational effectiveness and leadership to their core competencies requires, for some, a change in focus. Many PE firms have squads of operating partners whose job it is to oversee and assist portfolio companies during the holding period. The operating partner role is longer established than that of the human capital partner and is increasingly widespread. However, many operating partners are overstretched, asked to oversee a dozen or more portfolio companies. Furthermore, generally speaking—and, traditionally, appropriately—their background is often lighter on the “soft” skills of leadership, culture, and managing people. They, too, need support, not just from their firms, but also by being able to leverage specialized outside expertise.

Leadership teams that are effective over time not only have the right mix of skills and capabilities but also work well together and help shape a value- and growth-oriented culture in their organization above and beyond a perception of focusing on taking out costs. But both our firms have found that leaders now realize how much culture influences financial results and that companies and investors will benefit from paying more attention to this operating reality, too. This can mean taking time to align not only leadership incentives with organizational goals but also cultural priorities and ways of working for the whole organization.9

Longer holding periods, increased strategic focus on add-ons and roll-ups, and a volatile business environment are all here for the foreseeable future. In that context, advanced PE firms are already seeing benefits in shifting their approach to portfolio company management to a multidimensional focus that can adjust processes, incentives, leadership development structures, and behaviors as needed. These firms’ knowledge and example can provide best practices others can adapt to their own opportunities to thrive today.

About the authors

Will Moynahan (wmoynahan@heidrick.com) is a managing partner of the Private Equity Practice across Europe & Africa; he is the partner in charge of the London office.

Mark Veldon co-heads AlixPartners in EMEA, having formerly led AlixPartners’ EMEA Private Equity Practice.

References

1Ted Bililies, Madalyn Miller, Jason McDannold, and Clark Perry, “Tenth annual PE leadership survey: Leadership Under Pressure: Aligning Growth and Efficiency,” AlixPartners, March 25, 2025, alixpartners.com.

2 “CEO and board confidence monitor 2025: Persistent concerns, pockets of increased confidence,” Heidrick & Struggles, February 5, 2025, heidrick.com.

3 Ted Bililies, Madalyn Miller, Jason McDannold, and Clark Perry, “Tenth annual PE leadership survey: Leadership Under Pressure: Aligning Growth and Efficiency,” AlixPartners, March 25, 2025, alixpartners.com.

4 Heidrick & Struggles’ confidence monitor survey, 2025, n=928; and Heidrick & Struggles’ confidence monitor survey, 2024, n=3,019.

5 Ted Bililies, Madalyn Miller, Jason McDannold, and Clark Perry, “Tenth annual PE leadership survey: Leadership Under Pressure: Aligning Growth and Efficiency,” AlixPartners, March 25, 2025, alixpartners.com.

6 Heidrick & Struggles survey of CEOs and board members, March 2025, n=1,421.

7 Heidrick & Struggles’ CEO and board confidence survey, June and July 2024, n=1,702.

8 Heidrick & Struggles survey of CEOs and board members, July 2024, n=1,702 global respondents across sectors and markets; Heidrick & Struggles survey of CEOs and board members, 2025, n=522 global respondents across sectors and markets; and Ted Bililies, Joshua Tecchio, and Mark Veldon, “Third annual PE leadership survey: Misalignment between private equity investors, portfolio company CEOs triggering costly turnover,” AlixPartners, March 21, 2018, alixpartners.com.

9 Rose Gailey, Ian Johnston, and Holly McLeod, “Aligning culture with the bottom line: Putting people first,” Heidrick & Struggles, July 24, 2023, heidrick.com; and Ted Bililies, “Culture is key to success (and failure) in private equity deals,” AlixPartners, March 17, 2020, alixpartners.com.