Boards & Governance

Five Challenges Facing Today’s Board Chair: Insights from FTSE Chairs

Boards, like the organizations they steward, are facing an ever-increasing scale of challenges: new governance rules; digitization; the increased focus on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues; and the changing geopolitical environment. The COVID-19 pandemic has compounded these challenges with the economic and social disruption it continues to create. In this context of resetting businesses on the path to growth, the importance of the board to the business’s success, and particularly the role of the board chair, becomes ever more important.

We spoke to 29 chairs of current FTSE 100 and 6 chairs of FTSE 250 companies, some of the largest public companies listed in the United Kingdom.1 (See sidebar, “FTSE 100 chairs: A snapshot.”) We wanted to understand how their role has been evolving and whether the profile of the board chair has changed in the past three years to adapt to these complex challenges.

Though each chair has had a unique experience, the picture from our conversations shows that while the fundamentals of the role remain unchanged, the evolving mandate of the board has added layers of responsibility that require chairs to be more externally focused than ever. We also found that it is increasingly difficult for chairs to strike the right balance of power between boards and executive teams in a context where role boundaries are not always clear. While the challenges are many and varied, we distilled what we heard into five challenges for today’s chairs.

Challenge 1: Blend the view of today, tomorrow, and beyond

The recognition that businesses have to serve all stakeholders has been building progressively over the past decade. One chair captured the situation best: “We need to think about capital working for others than just shareholders; that leads us to the notion of purpose. Why are we here? What is our impact? Mission statements were always there; nothing is new, but the difference is on emphasis. It now feels fundamental.” The tension between long-term strategy and short-term returns has been amplified by the consistent increase in pressure from governments, consumers, employees, and other stakeholders to factor digital, purpose, diversity and inclusion, and sustainability into decision making.

Sustainability has become more urgent, with one chair explaining that “the eyes no longer glaze over when the ESG topic comes up—instead, they display some real anxiety.” While chairs raised some concerns regarding the ability of the corporate world to stay focused on sustainability in the wake of the pandemic, signals indicate that many companies are sticking to their ESG commitments.2 However, a recurrent frustration is that, while investors demand focus and transparency on ESG issues, that rarely translates into support for decisions that might mean reduced returns. Most investors have yet to expand their traditional three-year horizon for returns. As a chair noted, “Connecting the world we live in and are trying to operate in with a fund management industry that talks about it, but doesn’t believe it, is quite a difficult world to navigate.”

The difficulty of blending different time horizons and stakeholder expectations is amplified by the accelerated pace of change. Increasingly, boards are being forced to think more creatively. “The concept of three-to-five-year plans is going out the window,” one chair said. “Boards are looking for a more dynamic and agile way of thinking about the many bets they have to place on technology, on the consumer brand, and on people.”

Challenge 2: Secure tried-and-tested skill sets and assemble a diverse team

The best boards determine their composition in terms of the mix of skills and experiences required to meet their companies’ long-term strategic needs. Shareholders prefer a proven track record of impact. “We need to make sure we have the right mix of people thinking of the five-year strategy with a five-year horizon view,” one chair explained. Boards should complement traditional profiles with new skill sets such as digital, cybersecurity, consumer behavior, and, at times, even negotiating, coaching, and mentoring, as well as the recent need for restructuring expertise. (For more, see “Restructuring expertise: Bringing a new voice to the boardroom.”) Finding such people will likely mean looking in less traditional candidate pools, such as consulting, the public sector, academic institutions, and legal and trading bodies—with the caveat that potential directors need to understand how to run a business and have done it before.

Adding more women in the boardroom increases age diversity and contributes to the surge in digital and cybersecurity skills brought by some newly appointed directors in FTSE 350 companies. (For more on diversity in European boardrooms, see Board Monitor Europe 2020.) For consumer companies, women also bring a much-needed customer representation. Said one chair, “I think that the focus on gender has also had a derivative plus, which is age diversity. Because women who join boards tend to be younger, they are more street savvy when it comes to the consumer and more in tune with the age of a business’s consumer.”

While boards have become more gender diverse, the efforts toward racial and ethnic diversity have so far been less successful and are in need of more creative solutions. Adding and recognizing cognitive diversity is an even wider gap that boards need to address, as one chair noted: “Diversity is hugely important, but to me, it’s more about the skill set, not defined by gender or ethnicity. It’s important not to have a single prism of experience.”

When it comes to the role of the chair itself, successful candidates continue to come from a pipeline of chief executives and CFOs. Seventy-seven percent of FTSE 100 chairs have had a CEO and/or a CFO role, and the newest cohort appointed in the past three years shows a similar trend, at 79%. Most chairs see these roles as the only way to get the experience of running a large business and making high-stakes decisions. As one chair said, “It is difficult not to have the experience of running a business to carry the trust of investors. A chair has to understand the business.” But some also point out that former CEOs don’t automatically make good chair candidates. “Moving to a role where you have little power but where you need to influence is a challenge,” noted one chair. Others see a clearer path for CFOs to the role, particularly in the aftermath of a severe economic downturn when companies are focusing on efficiencies and cost-cutting. According to one chair, “The future is looking bright for CFOs who want to become chairs; the risk-averse climate will do them well.”

As the diversity of boards improves, some chairs are optimistic about seeing the increased board diversity eventually reflected in the top role. “In due course, the increased diversity of board directors will play a part in changing the mix of backgrounds for chairs,” said one chair. “But for the foreseeable future, CEOs and CFOs will still dominate.”

Challenge 3: Balance inclusion, challenge, and debate

Every chair wants a harmonious boardroom. But gathering and including diverse opinions should and will create more challenge and disruption. Chairs agree that they need to encourage cognitive diversity and healthy debate. Said one chair: “It’s important, as a chair, to allow the free thinking a board needs to foster different viewpoints. Diversity is an attitude, inclusivity is an attitude, and they must go together.”

An inclusive culture means a safe space to share views and debate. “Chairs need the right skill set to be able to bring diversity to the fore,” explained a chair. “That takes a collaborative, encouraging, and participative style.” They should also make sure that new board members, particularly first-time directors, are onboarded in a systematic manner and empowered to contribute early on in their role, because some directors might come from totally different backgrounds. As one chair pointed out, “If you have moved away from the traditional FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 pool of directors, then new board members do not have the same terms of reference, particularly if it is their first board.”

Ultimately, an inclusive and effective board is built around a shared purpose, which requires breaking down barriers and establishing principles of engagement based on trust and transparency. The only way this can be achieved is if individual members get to know one another and take opportunities to explore each other’s perspectives in good faith.

Beyond the internal boardroom dynamics, some chairs also raised managing the involvement of activist investors as part of the overall dynamic. One chair attributed activist shareholders’ interest to the fact that companies had lost touch with their investors: “They buy 5% of the company but are only effective if they get another 45% of shareholders supporting them. A board that gets far away from its shareholders gets activists. And if the activists have a more credible plan than the board does, things need to change.” As stakeholder activism reignites in many markets, the pragmatic approach for chairs is to factor their views into the decision-making process and be very transparent about the reasons and impact of those decisions.

Challenge 4: Find the right successor through the new regulatory maze

How long should a chair serve on a board? And how can he or she find ways to develop a more diverse group of people to succeed in the role? Opinions are divided. Today’s regulations in the United Kingdom for public companies require chairs to step down from their roles once they have served on a particular board for 9 years, including time served as a board member. Opinions are split between those chairs who see this as “an amazing piece of corporate governance, which saves having very difficult conversations,” to others who have found it “surprising and unhelpful. It has cut across a number of well-planned successions and has made internal succession much more difficult.” The average tenure of current FTSE 100 chairs is 4.2 years, and for those who had previous tenure on the same board, the average time to be appointed chair was around 6 years. Should that trend continue, it gives homegrown chairs only 3 years in the role, on average.

This is of particular concern when it comes to women’s opportunity to become chairs. The more common route to a chair role for women is through the board rather than executive experience. “I don’t think the nine-year rule helps us to appoint more women chairs,” said one chair. “The route for many women to chair is a senior independent director position, and it is likely that it will take three to four years for the board to think they are competent for the position.”

Another regulatory challenge that chairs brought up was about remuneration, particularly pay restrictions and the requirement to publicly disclose salaries and fees. Obviously, lower compensation for directors reduces boards’ ability to attract the right people for their team. Said one chair: “Remuneration is an issue for global businesses, particularly for the pay of the CEO and CFO and board members but also for non-executive directors, and a good example of that is when you want a US director on your board.”

Chairs need to start mapping potential successors as soon as they take over the role and anticipate what the role will entail a few years down the line. Visionary chairs will look deeper into organizational levels to identify potential CEOs and other senior executives and make sure they have earlier exposure to the boardroom and widen the talent pools by working with the executive team in building a pipeline of potential candidates earlier in people's careers.

Challenge 5: Know the detail but don’t get too close

There is increased scrutiny on non-executive directors from regulators and stakeholders. For example, in financial services, the Senior Managers Regime mandates personal accountability of senior leaders and makes chairs legally responsible for incidents such as fraud, unethical behavior, and corruption. This motivates them to be more engaged with the culture of the companies they lead. In addition, the overall heightened demands on their time, particularly in times of crisis, also make the case for closer involvement, bringing the chair deeper into the fabric of the organization.

At that end of that spectrum, some chairs are suggesting the need to have an office in the building, in a way that doesn’t undermine or disrupt the role of the CEO. This could be a tenuous balance to maintain and would require a clear mutual understanding of roles and responsibilities of the two leadership positions and a strong relationship of trust between the two individuals. If successful, it could be a boon for the CEO, who could benefit from a trusted adviser and sounding board in close proximity. But it is possible that the risks of a more tense relationship could outweigh potential benefits if CEOs feel they don’t have the space they need to lead. As one chair noted, “The chair should not interfere with how the CEO does his or her job, but the chair can test the temperature of the organization and also demonstrate his or her level of engagement.”

One area of potential role overlap is representing the company externally. Recent events have seen CEOs taking a clear stand and speaking up on issues that, 5 or 10 years ago, would have been relegated to the communications office. These issues include the current climate crisis, systemic racial injustice, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Chairs having a more external role would require a close, trust-based partnership with the CEO. But chairs have already seen a change in that direction; some pointed out that their dynamic with the CEO has changed from a linear, meeting-based conversation to a more ad hoc interaction and one focused on external events. “We used to discuss the agenda, and it was quite linear,” said one of the chairs we spoke to. “Now, a CEO will call the chair [to talk about] what is going on externally.”

Conclusion: What should chairs do?

As the role of the chair will likely evolve ever faster, chairs need to be prepared to keep adjusting the way they lead. Much in the way that bringing more women onto boards has often changed the tone and process of decision making, appointing more board members from different cultures and ethnicities will have a similar effect: some cultural norms come with more bias toward action and others toward reflection, and there are varying degrees of readiness to express a point of view, especially one that challenges perceived authority or collective norms.

Outside the boardroom, the chair role is becoming more involved with the business and requires a better understanding of its stakeholders, particularly customers, shareholders, and activist investors. And the newer regulatory challenges make the process of succession planning more complex.

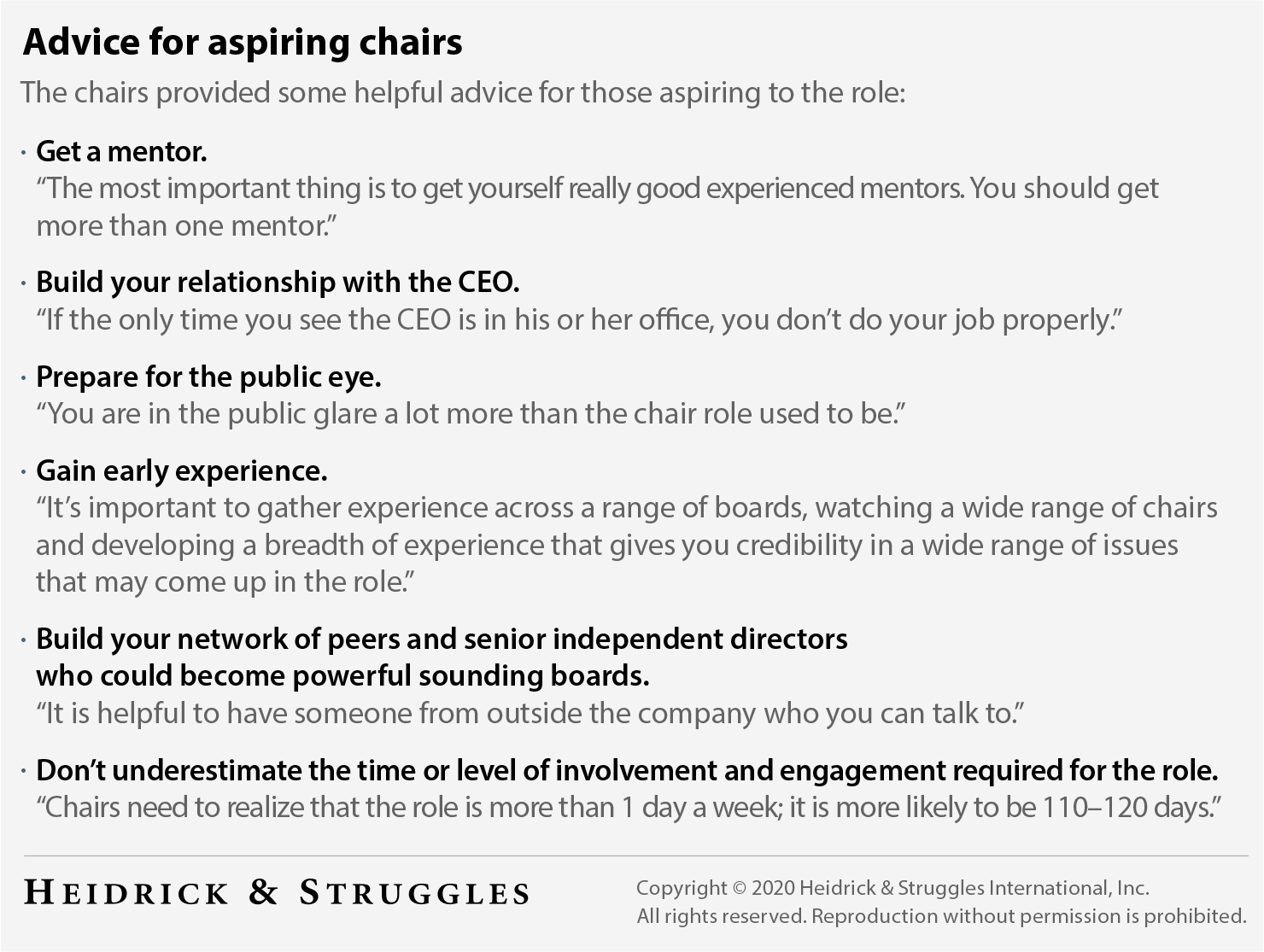

As we have learned from our conversations with chairs, the scope of change is different for each organization and each board. It develops at different speeds and in different patterns. One thing is certain: the job is unlikely to become any easier. One piece of advice offered stands out as the starting point for aspiring chairs: “Make sure you know what you are wishing for. It is hard work, and there is more exposure than many would want.”

About the authors

Alice Breeden (abreeden@heidrick.com) is the leader of Heidrick Consulting’s Center of Excellence in CEO & Board and Team Acceleration; she is based in Heidrick & Struggles’ London office.

Will Moynahan (wmoynahan@heidrick.com) is partner-in-charge of the London office and regional managing partner of the CEO & Board and Private Equity practices for Europe and Africa. He is also a co-leader of the CEO & Board Practice in the United Kingdom.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Will Everett and Kate Rankine for their contributions to this report.

They also wish to thank the board chairs who shared their insights for this report:

John Allan, Chair of Tesco PLC; Kevin Beeston, former Chair of Taylor Wimpey plc; Lord Blackwell, Chair of Lloyds Banking Group plc; Stuart Chambers, Chair of Anglo American plc and Travis Perkins plc; Sir Ian Cheshire, Chair of Barclays Bank UK PLC and Menhaden PLC; Andy Cosslett, Chair of Kingfisher plc; Annette Court, Chair of Admiral Group plc; Adam Crozier, Chair of Whitbread PLC and ASOS Plc; Sir Ian Davis, Chair of Rolls-Royce Holdings plc; Irene Dorner, Chair of Taylor Wimpey plc; Jan du Plessis, Chair of BT Group plc; Andy Duff, Chair of Elementis plc and former Chair of Severn Trent Plc; Javier Ferrán, Chair of Diageo plc; Sir Douglas Flint, Chair of Standard Life Aberdeen plc and IP Group Plc; Sir Peter Gershon, Chair of National Grid plc; Richard Gillingwater, Chair of SSE plc and Janus Henderson Group plc; Nigel Higgins, Chair of Barclays PLC; Glyn Jones, Chair of Quilter plc; Lord Livingston of Parkhead, Chair of Dixons Carphone plc; Ken MacKenzie, Chair of BHP Group; Andy Martin, Chair of Hays plc; Fiona McBain, Chair of Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust PLC; Kevin Parry, Chair of The Royal London Mutual Insurance Company Limited; Richard Pennycook, Chair of Howden Joinery Group Plc and On the Beach Group plc; David Roberts, Chair of Beazley plc; Mike Rogers, Chair of Experian PLC; Mike Roney, Chair of Next plc and Grafton Group plc; Richard Solomons, Chair of Rentokil Initial plc; David Tyler, former Chair of Hammerson plc; Baroness Vadera, Chair of Santander Group Holdings plc; José Viñals, Chair of Standard Chartered PLC; Paul Walker, Chair of Halma plc and Ashtead Group plc; and Mark Williamson, Chair of Spectris plc.

References

1 The interviews took place mostly before the COVID-19 crisis impacted business operations.

2 Attracta Mooney, “ESG passes the Covid challenge,” Financial Times, June 1, 2020, ft.com.