Chief Executive Officer

Lessons from Ukraine’s wartime CEOs on leading through crisis

The war in Ukraine with Russia, beginning with the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and becoming nationwide in February 2022, has forced every Ukrainian CEO and leadership team to learn how to mobilize their organization, radically change their strategy, and transform their business.

A year after the outbreak of full-scale war, we began to interview CEOs who lead large-scale Ukrainian businesses in various sectors of the economy in order to understand their leadership journeys: the stages of guiding an organization through a time of war, how these leaders’ behavior has changed, their motivations and footholds, and lessons learned. The insights into how these CEOs and their companies have remained resilient and future focused in the worst of circumstances can serve as a guide and support for other leaders who face new challenges on a daily basis and strive for success in the face of danger and uncertainty.

The stages of responding to the war

1. Underestimation of the threat

Most CEOs admitted that they had seen objective signs of a threat several months before the invasion began. But even those who were preparing did not believe they would face a full-scale war. One CEO aptly expressed the experience of many: “We all noticed this heavy cloud of threat hanging over us, but we didn't pay enough attention to it.”

At most companies, the CEO and a small group of crisis planners had developed two or three scenarios dedicated to various options related to the invasion of separate territories of Ukraine, based on past experience. Oleksandr Pysaruk, CEO and chairman of the board of Raiffeisen Bank Ukraine was one of the few who began preparing for a full-scale invasion. He began planning in late 2021—despite the fact he did not believe it would really come to war. Other executives planned for a full-scale invasion only in general terms. However, even those plans proved valuable. Lidiia Ozerova, crop protection business unit lead at Syngenta, said, “We planned all the scenarios carefully—even the worst, although not detailed, as we did not believe in this. And it saved us.”

2. Short-term shock and a quick transition to action

Everyone experienced the emotional shock of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. However, from the first minutes, even while most CEOs were still in their own homes, they switched to instant decision-making, information exchange, and constant monitoring of circumstances. Their first steps were ensuring constant online communication with their teams and evacuating employees and others from high-risk areas. Many of the leaders were also able to provide additional information to the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine regarding the situation in the occupied territories and the movements of the Russian troops.

Over the next several days, many CEOs decentralized power in their organizations, significantly increasing their delegation of authority to managers and employees on the ground. Some had started down that path before the war, as Oleksandr Komarov, CEO of Kyivstar, explained: “My role as a leader is to develop a system of collective decision-making and ensure a culture of delegation and the absence of fear to speak frankly and act by example. We had all this before; that's why we were able to cope with the war crisis.” Syngenta’s Ozerova added, “It was important to let the leadership of others manifest itself.”

Not everyone took that approach, however. Igor Smelyansky, CEO of Ukrposhta, said, “I do not believe in a collective decision-making body. We are changing the management model to a more centralized one.” But he also admitted that “there must be a balance between dictatorship and delegation.”

It was also very important for the leaders of the organizations to receive extended powers from the shareholders or boards, as Kyivstar’s Komarov said: "I received a mandate of trust to act independently." The CEO of a large European business, meanwhile, described negotiations with headquarters regarding obtaining extended powers as simply, “I confronted them with the facts.”

3. Adaptation to war conditions and maintaining business continuity

“The first months of the war felt like the uncertainty of a black hole combined with the belief that we will withstand,” said Dmytro Kashpor, CEO of Adama Ukraine, describing this phase of adaption.

In April and May of 2022, it gradually became clear that the dedication and courage of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, the Territorial Defense Forces, volunteers, and Ukrainian citizens meant that much of the country would not be occupied. CEOs were better able to understand the conditions in which they were now operating their businesses. At that time, as in peacetime, Glovo couriers returned to the streets of Kyiv to deliver food. Internet memes of them became an inspiring symbol of the vitality of Kyiv. At this stage, the CEOs and management teams focused on restoring production, optimizing business processes, and simplifying organizational structure. Said Kyivstar’s Komarov, “We removed everything unnecessary, including some elements of corporate management.” Leaders also gradually renewed their efforts to develop teams and employees for the longer term.

For many companies, access to new markets and customers outside of Ukraine through new opportunities, innovative solutions, and new business models and products became a sort of salvation. Flexible external partnerships with state institutions, the General Staff of the Armed Forces, volunteer organizations, and sometimes even competitors spread dramatically. “We are not competitors now, but Ukrainians,” said Vitalii Vereshchagin, CEO of Caparol Ukraine. An example of this was the temporary contract manufacturing between Imperial Tobacco and Philip Morris, as the Philip Morris factory in the Kharkiv region had to stop its work due to hostilities. There was also the organized national roaming among three mobile operators—Kyivstar, Lifecell, and Vodafone—that was launched together with the state services. Vodafone subsequently developed mobile base stations equipped with Starlink and shared this innovation with other mobile operators.

A look toward the future

Most of the CEOs we talked with in the spring of 2023 were preparing for a return to liberated territories, and a few had even begun their preparations at the preliminary stages. Leaders, together with their teams, are anticipating the possible needs of residents and market challenges and are developing new strategies, operational plans, and products. The quick opening and resumption of work in the liberated territories of branches of system organizations such as Ukrposhta or PrivatBank is of great practical importance for citizens and infrastructure.

How CEOs changed their behavior

All the leaders we interviewed identified two key priorities from the time they started preparing for a possible invasion to now: putting people first and ensuring business continuity.

1. People first

The safety of employees’ lives has become an absolute priority for CEOs. Most shared numerous examples of unquestioningly making decisions in favor of people's safety, allowing material losses. And that included not only employees but also customers and any citizens who came into their sphere of influence and needed help. Yevhen Kobets, CEO of Imperial Tobacco Ukraine, said, “At that time, our company became a great point of resilience for employees and their families.” Each of the leaders interviewed could say the same.

2. Business continuity

The next critical priority was ensuring business continuity. This meant not only the production, provision of services or goods, and implementation of changes in the company but also saving jobs and supporting and motivating people both mentally and financially. CEOs who were already leading with more flexibility and empathy and those who were most involved in operations and strategy before the invasion took care of business continuity planning most successfully.

In parallel with CEOs’ focus on keeping businesses going, employees of many organizations demonstrated incredible dedication. Despite the persistent efforts of managers to ensure the safety of their people by offering them the option to work in other areas, many employees refused to flee, even in the face of evacuation orders, and chose to stay in dangerous areas, including those being bombed, because it was important to them to do their best to ensure the functioning of critical services. Because of the bravery and commitment of these employees, mobile service and communication were possible. When armored collection vehicles were not available for the transfer of money, elderly people were still able to receive their pensions when employees transported money to branches in private cars. Watching how employees of the Continental Farmers Group worked during the war, the CEO, Georg von Nolcken, said simply, “I understood Ukraine.” Von Nolcken, a German, was one of several ex-pat leaders who refused to leave Ukraine after the full-scale invasion. He said, “I stayed. Because otherwise, I would feel that I betrayed [Ukraine].”

Adapting behavior

To meet the two priorities of people and business continuity, the CEOs we spoke with said they reinforced or added several specific behaviors:

Concentrating on the here and now: This means living every moment to the fullest, being open to what is happening, and being present in the current moment. Ukrposhta’s Smelyansky explained: “Every CEO should realize that this day could be the last.” Being able to be in the present was one of the most important things that helped CEOs invest their energy in solving critical problems consistently, making crisis decisions, and achieving results in situations of uncertainty. It helped them overcome constant stresses without accumulating them too quickly. “The war got under the skin. And it will never end for me. I take it calmly,” said Adama Ukraine’s Kashpor.

Making high-speed decisions: In situations of threatening uncertainty, the speed of effective decisions can overtake a search for the best solution. Every CEO we talked with said that the speed of their decisions increased dramatically with the onset of the invasion. In order to solve an urgent problem immediately, they deliberately took risks and allowed themselves to make mistakes. For some CEOs, that came quite naturally, while others had to learn from experience. Several managers admitted that making crisis decisions became easier for them, as “everything becomes black and white because you clearly see who the enemy is.” Now, though, some leaders are wondering how this enduring black-and-white perception will affect their personalities in the future. They wonder whether they will lose the ability to perceive reality in the entire spectrum of colors after the war.

Communicating 24/7: The dramatically increased scope of communication for information sharing, support, personal influence, and inspiration became one of the key tools of CEO leadership beginning with the first hours of full-scale war. Syngenta’s Ozerova said, “It was important to engage people into work, to ensure progress in small steps with positive results, and to give them light ahead—the vision.” Communication was first and foremost with shareholders and employees, from the headquarters to frontline sellers or cashiers. But it was also important outside the company, with state and non-state institutions, partners, military officers, and volunteers. In some cases, it was a two-way street—some leaders admitted, for example, that communication with volunteers and the military inspired them to continue their hard work and supported them at the most difficult times.

Setting a personal example: Like any life crisis, war is a test of authenticity, a time to be and not to look. Many managers consciously or spontaneously chose by their own example to broadcast their true values, hope, and vitality. They inspired and supported others. Through this personal communication, employees directly perceived the authenticity of their leaders’ values, decision-making priorities, emotional openness, and restraint—manifestations of their confidence and vulnerability. This strengthened the mutual trust and leadership influence. Some leaders, such as Ukrposhta’s Smelyansky, personally visited areas close to the occupied territories and the front line in order to support employees and customers. These visits also helped him obtain information for making appropriate decisions—decisions that would be less effective if they were made from a secure office.

Speaking with radical candor: Being as honest as possible allowed most of the leaders we spoke with to increase the speed of decisions, maintain trust, reduce anxiety, and bring transparency and acceptance of leadership decisions into communication with their teams and subordinates. This frankness often applied to headquarters, shareholders, and the board. As one of the CEOs said about his negotiations with the company's head office, “I didn't have time for diplomacy.” Adama Ukraine’s Kashpor is convinced that “We have become more demanding, practical, and straightforward—I see this in Ukrainians now. We take care of our people, our home, and our country.” At the same time, leaders noted that radical candor should always include an empathic attitude.

Embracing empathy: CEOs became much more empathetic both in communication and in decision-making, developing an increased ability to perceive and understand the emotional states of others. Caparol Ukraine’s Vereshchagin said, “I was the most humane in the role of CEO during all this time of war.” Even during our interviews, it was noticeable how some powerful leaders changed their communication style toward softness and sensitivity. Some leaders openly admitted this.

“I feel my own fragility. I have become kinder,” said Olga Ustinova, CEO of Vodafone Ukraine. “Mutual trust with the team has become greater.”

Being willing to change: Executives who coped successfully with the war crisis were open to new opportunities and strategic changes in the company's activities. This made it possible to preserve, maintain, or develop a business or transform processes or structure, and to learn from experience at speed. Syngenta’s Ozerova said, “We quickly realized that the market would change fundamentally, and we started transforming processes, building a new business model, and opening new directions.” Caparol Ukraine’s Vereshchagin said, “We significantly changed the model—we quit our own retail, and we gave up direct sales.”

What got CEOs through

Yuriy Golianych, general manager of household, recycling, and international business at Biosphere Corporation, shared that “it is important to preserve yourself as a person.” Constant emotional stress and a heavy workload led some CEOs to the verge of exhaustion a year after the start of the war. A marathon of openness, communication, personal accountability, and making decisions with speed and uncertainty led to the gradual accumulation of mental and physical fatigue, and some CEOs said they feel on the verge of burnout. But all are holding on. When talking about what helps them maintain their personal energy levels, almost all of them mentioned a few fundamentals:

Emotional connection with family members: Almost everyone emphasized the extreme importance of contact with their own family and loved ones. This was most often the first thing they mentioned.

A big objective: The vast majority of CEOs talked about the mission they undertook during the war together with their teams and organizations as a whole. This is the answer to the question: “What am I enduring all this for?” Adama Ukraine’s Kashpor said, “You follow your heart and what is happening in Ukraine, for the sake of the children who will live in this country.” This is the same authenticity and genuineness that comes about when people do not only declare the mission but really live it in their choices and concessions. One of the managers of a large retail chain said simply, “I really felt the national scale of our impact on the food security of the entire country.”

Self-care: Within the first months and even days of full-scale war, CEOs were focused mainly on crisis processes, saving people, and communications. However, once things were relatively stable, they began to realize that it is increasingly difficult to remain efficient in such exhausting conditions. Therefore, they gradually renewed their attention to the quality of their own lives and began to find more time for their personal mental and physical health needs. They began to allow themselves to sleep more, engage in moderate physical activity, pay attention to diet, and engage the possibility of entertainment such as reading and socializing.

How these lessons CEOs have learned can help others

Some leaders, such as Raiffeisen Bank’s Pysaruk, already had considerable leadership experience during large-scale socioeconomic crises. These leaders recognized that without this experience it would have been more difficult for them to lead their companies through the war. But we can only hope that most CEOs will never have to learn from similar experiences. With that hope, the insights from all 15 CEOs we talked with can help prioritize—among capabilities that are central to all good leaders—those that will most help other leaders in crisis, whatever the specifics of the crisis and their organization.

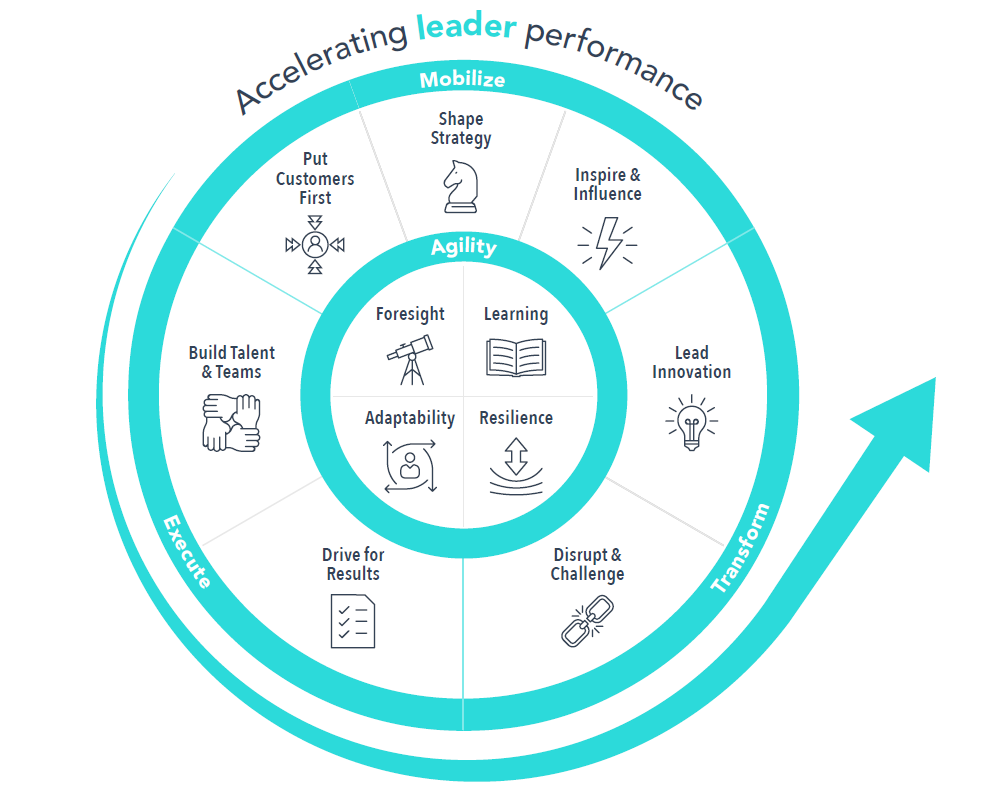

Our overall leadership model consists of 11 drivers of performance:

It is no surprise that under the circumstances of the war, many of the capabilities that made the most difference for the CEOs we talked with relate to mobilizing and agility. For example, communicating 24/7 with radical candor and empathy aligns with inspire and influence. Making high-speed decisions and being willing to change align with agility. The examples of Ukrainian CEOs can inspire other leaders to find their own ways to build and deploy the same capabilities—and maintain their own stability and ability to be a role model in the service of reaching big organizational goals.

More generally, Ukrainian CEOs’ key lessons learned during this time and the advice they would give themselves and others can help their peers learn how to cope with crises. The points that came up consistently include the following:

- Always plan for any scenario that has a probability greater than zero, even if you do not believe it will happen.

- Make sure your leadership style reflects care for teams and employees.

- Delegate more and build trust between headquarters and leaders in other parts of the organization.

- Simplify organizational structure and processes to maximize efficiency today so they will be less likely to be barriers in a crisis.

- Focus on shaping the organizational culture, moving it toward humanity, cooperation, and flexibility.

- Bravely and quickly seize new opportunities.

- Cooperate across boundaries within and outside your organization.

About the authors

Oleksandr Kosterin (okosterin@heidrick.com) is a principal in Heidrick & Struggles’ Kyiv office and the head of leadership consulting in Ukraine.

Kateryna Soroka (ksoroka@heidrick.com) is an engagement leader in the Warsaw office and a member of Heidrick Consulting.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all 15 executives interviewed, named and unnamed, for their insights. Their views are personal and do not necessarily represent those of the companies they are affiliated with.