Leadership Development

Developing future-ready leaders: When—and when not—to invest in coaching

It is becoming increasingly challenging to find and retain good leaders. Faced with this, companies are recognizing many longstanding flaws in their executive development and succession planning processes, including how and why they offer executive coaching. Coaching can be a critical way to help leaders develop the mindsets and behaviors they need to succeed—but only 40% of executives are mostly or entirely satisfied with their company’s coaching offerings today, according to a recent survey we conducted of executives across functions.1 Indeed, we see many organizations over- or underinvesting in coaching or applying it to leaders and teams without clear standards or criteria for doing so. It’s no surprise, then, that many organizations are seeing less than satisfying results.

In our experience, when companies apply three criteria as they think about who and when to coach, coaching can be a tool that brings value both to individuals and to organizations. The three criteria are: that the mindsets or behaviors leaders need to work on developing are in fact coachable; that the leaders must themselves be at an inflection point; and that the leaders must have already demonstrated a capability to take in feedback and change. It is when these conditions aren’t met that coaching can become a significant investment with questionable value and outcomes for the organization, even if the leader receiving coaching appreciates the experience.

How companies are using coaching today

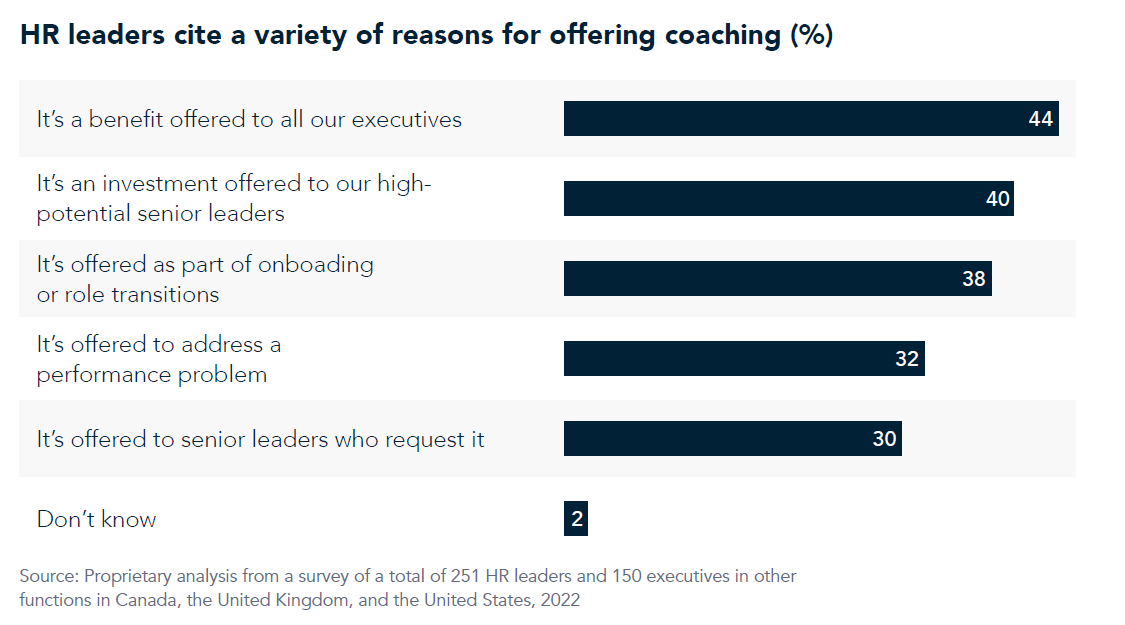

Over decades of work across industries, we have seen no consistent standards regarding how and to whom to offer coaching. Sometimes it’s left up to managers or the board; sometimes it’s offered because of a performance issue or as a blanket benefit for high performers; sometimes it’s simply offered to anyone who requests it. Our surveys2 underscored the wide range of reasons companies offer coaching.

Given this inconsistency, it’s not surprising that 79% of HR leaders say their coaching offerings are somewhat connected, at best, to their leadership development programs. Or that executives, for the most part, are not entirely satisfied with their company’s coaching offerings.

However, as leadership development and retention becomes a more pressing need than ever, companies can’t afford not to make every investment as effective as possible.

When coaching actually works

Coaching done most skillfully is distinct from other related development practices such as training, consulting, or mentorship. Coaching is not about transferring knowledge but about drawing potential out of someone that’s already there but not being deployed. In true coaching, the coach’s job is to ask the right questions and to support and challenge the leader's thinking, while the leader does the actual problem-solving work. Coaching, then, is a sustainable form of development; if the leader has already done the hard work of problem-solving in the coaching context, the next time an issue arises or they need to reach for a specific capability they’ve developed, they can find it independently. Of course, from time to time, a coach may offer a perspective or help a leader answer a question. But if knowledge transfer is the main need for a leader, coaching is not the right avenue.

In practice, this means a coach will sit down with a leader and ask questions. For example: “You want to work on decision-making and prioritization. What are the issues there? What have you tried? How is that working?” Leaders may be frustrated by this approach at first, but, as one CEO said to their coach, “When we started, all your questions were annoying, until later I realized you were challenging me to challenge my assumptions, which I did, and that helped me shift how I lead this company.”

That understanding of coaching’s role is what makes the three aforementioned criteria relevant.

When the leader’s development need is coachable

When targeted well, coaching is appropriate to build on strengths, address a gap, or both, in the context of how a leader affects others. This is because many leaders have blind spots of some kind regarding how their leadership approach may be getting in the way of their team operating most effectively. For example, our work coaching CEOs often involves assessing and then optimizing how a CEO works with their board. Among leaders at other levels, coaching often relates to how they lead their teams. Frequent coaching needs include building greater clarity in communication, making decisions either more rapidly or more deliberately, and balancing “hands-on versus hands-off” management. Fundamentally, what is coachable is what can be addressed by supporting and challenging a leader to think and operate differently but still well within their character and personality. Coaching won’t help leaders change their stripes to spots, rather, it will help them think and operate with an enhanced set of tools and a shifted point of view.

For example, many years ago, the CEO of a growing healthcare company had been given feedback as part of their coaching work about being a micromanager, while he expressed frustration about his team’s inability to be autonomous. “You can’t buy a coffee pot for the break room without his approval,” a colleague said. Indeed, the company’s rate of growth was limited by the CEO’s involvement with everything. A coach helped the CEO realize that his mindset was rooted in the notion that he couldn’t take a day off or everything would come skidding to a halt. His coach then challenged him: “Is this mindset going to lead to the result you want?” And then, “What mindset will enable you to optimize your time and your team’s time when it comes to decision approvals?” Ultimately, the CEO realized he needed to trust that his team was capable and let them operate independently. And, critically, he arrived at that solution on his own. When his mindset shifted, the limitations in the growth of the company were removed; it quadrupled revenue over three years with healthy margins. And the CEO was finally able to take a vacation.

When the leader is at a learning inflection point

An inflection point can be any number of things—someone could be joining a company or taking on a new role, be in line for a promotion or recently promoted, or have just gotten some important feedback and be welcoming of support to address it. Examples include a moment of realization (“Wow, I really need to show up differently with my teammates”), challenge (“We challenged him to think about scaling his leadership by letting his team do more of the day-to-day”), or dissonance (“I got some feedback that the conflict I’m having with my CFO is making the wrong waves”). Whatever it is, the leader and the organization must both recognize that the leader has a learning need or an opportunity to make some sort of adjustment. These inflection points are the right fuel in the tank to spark the focus and learning needed for coaching success.

This is because, as humans, we learn and evolve—or not—in similar ways over time. The Swiss psychologist and states of ego development researcher Dr. Susane Cook-Greuter explained adult development as follows: “Overall, world views evolve from simple to complex, from static to dynamic, and from egocentric to socio-centric to world-centric.”3 This progression in earlier stages is propelled by pain—situations that challenge our ability to make meaning—and in later stages by the ongoing desire to learn and evolve.

Many executives and leaders fall into the middle of that continuum and, unless there’s a real need for change, they won’t, because how they operate has been successful so far. Just wanting coaching because it’s a perk, or wanting high performers at the organization to get coaching, isn’t tied to lasting improvement often enough to justify the investment for organizations (though there’s no reason not to encourage such people to seek coaching on their own).

And an inflection point is not only a general need for change. It needs to be defined by specific goals—a defined point A to point B in terms of what needs to change and the timeline for change. For example, one global consumer-facing organization was planning the CEO’s succession and had several potential internal candidates for the consideration, as well as external candidates. The inflection point was clear: an opportunity to become CEO. And there was a firm endpoint—the CEO’s retirement, at which point one of the three candidates might be given the job.

In the 18 months leading up to the CEO’s retirement, three candidates each received individualized assessments that, alongside board input and colleague feedback, identified specific development areas. Each leader developed individual coaching plans with up to three specific goals in mind. Across the leaders, these included “compelling board presentations and exposure,” “strategic operating on a global scale,” and “developing greater internal influence through followership.” Each of the leaders had a number of strengths already, and the need was to build on those strengths and, occasionally, to address a gap. While the board ultimately chose an outside CEO from a different industry with a track record of organizational transformation, each of the internal succession candidates received meaningful upgrades to their ability to lead, and all continue to be successful.

When the leader has a desire and capacity to be coached—and a track record of learning and changing

Finally, coaching is most effective when a leader is high performing, high potential, and has demonstrated an ability to learn, take in feedback, and evolve behavior and mindset over time, as the three CEO succession candidates did. So, when a coachable need comes up, they have already demonstrated a history of taking in feedback and operating differently, giving the company an indication that the investment will be worthwhile.

On the other hand, when a leader has a coachable need and is at an inflection point yet may be resistant to feedback, it’s fair to consider whether an investment in coaching is wise. For example, someone of whom it’s said, “They’re always asking for feedback and open to it, and you can see how they take it in and use it,” would be a better bet on coaching than someone of whom it’s said, “They tend to get super defensive when you point something out that wasn’t their own idea, and I haven’t seen that change in the years I’ve known them.” Similarly, someone who says, “I was ‘voluntold’ to get a coach because my CEO has one and she loves her coach, but who has time?” would flag an executive who may lack the capacity, time, or engagement needed to invest in coaching.

A real commitment to change is reinforced in effective coaching efforts when the leader being coached discusses with their direct leader—or a board member when the executive is CEO—the feedback they have received and the goals they have established to ensure their individual view and the organization’s view are aligned. Such a discussion may also include the timeline for achieving their goals and specific actions or steps they are likely to take to reach them, and can be a good opportunity to discuss any support they will need along the way.

In addition, the coach and the leader receiving coaching must not only identify but also adjust over time the intersection of the organization’s needs for that leader’s development and the leader’s own desired development areas. Insufficient focus on either will result in misalignment and will be unlikely to achieve a satisfying outcome.

What coaching looks like when these three criteria are in place

At her request, to help set her up for success in a new role, the incoming chief marketing officer of the largest division at a Fortune 200 global technology company was hired a coach. The coach started by getting grounded in what the executive thought was important coming into the role. She responded, “This is a relationship-driven company. So it’s going to be about building the right relationships from day one. There are a number of people who probably aren’t going to be delighted I got the job, and I need to collaborate with them successfully.” She and her coach spoke a lot about this mindset and the coach challenged the executive to frame up the practical behaviors of being focused on relationships in balance with tasks, why she thought this was important, and how she wanted to approach it. She believed building a resilient network would help her onboard and lead to sustainable success, in addition to early wins.

With the guidance of her coach, she identified the highest value relationships she needed to build and who she could ask to be her internal “truth tellers,” providing her honest feedback about her performance and inside information about culture. She followed that coaching plan closely, and heavily invested in relationship-building in addition to achieving some early wins with her team. The results? When she came in as an outsider at a very senior level, she had a clear understanding that she was an outlier in terms of potential consideration for the global CMO role in the years ahead. However, she evolved her leadership approach and built quite strong and resilient bonds with her colleagues. Skeptics and supporters alike would acknowledge that despite long odds due to being an outsider coming in at a senior level, she is well positioned for ultimate succession consideration.

Conclusion

Because coaching done effectively helps leaders learn how to solve their own problems and think through the mindsets they need to succeed, they will continue to reap benefits long after the coaching has ended—driving lasting value for themselves and their organization.

About the author

David Peck (dpeck@heidrick.com) is a partner in Heidrick & Struggles’ Los Angeles office and leads the Executive Coaching Practice.

References

1 Proprietary data and analysis from a survey of 150 executives not in HR conducted in summer 2022.

2 Proprietary data and analysis from a survey of 150 HR executives conducted in summer 2022.

3 Kyle Kowalski, “An Introduction to “Ego Development Theory” by Susanne Cook-Greuter (EDT Summary),” Sloww.